LETTER FROM MALMÖ

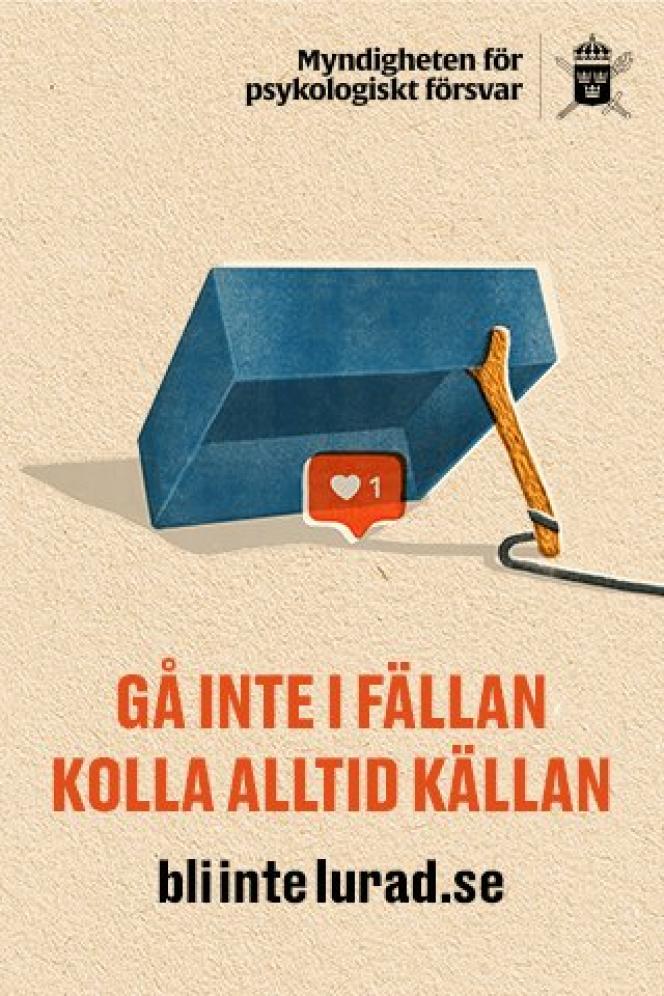

Since May 23, strange drawings, reminiscent of propaganda images from the 1940s, have adorned bus stops in Sweden. The same were published in newspapers or on social networks. We see the lid of a box, held by a stick, about to close on its prey. Below, a “like”, as found on Instagram. Another shows the head of a cat on the screen of a mobile phone, the shadow of which forms a monstrous silhouette. The message: “Bli inte lurad” – “Don’t be fooled”.

On the Internet, the three words form the address of a site, which offers – in Swedish, English and Arabic – easy tips for identifying misinformation. How to recognize a “fake”, for example. It is recommended to always check who the authors of a text or message are and ask why it was sent. A small glossary details the difference between misinformation, misinformation and misinformation. Terms such as “Potemkin village” (facade) or “sock puppet” (fake social media accounts) are explained there.

Behind this campaign is the Agency for Psychological Defense: an institution that has just risen from its ashes in Sweden, having been buried in the 2000s. At the time, the Scandinavian country was convinced that the fall of the Berlin Wall and the implosion of the USSR had definitively removed the war from the European continent. The army had been disbanded, military service abolished and total defense – developed to deal with total war – abandoned.

“Do not succumb to enemy propaganda”

The annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 set the record straight. Europe then rediscovered the effectiveness of destabilization: “In Donbass, Russia waged a hidden war, where disinformation and propaganda were used to deny the war, before admitting that it was taking place”, explains Magnus Hjort, head of capacity development at the newly formed agency. In Sweden, total defense is back in fashion and, with it, psychological defense.

Originally, it was designed “to enable the population to mentally cope with war, possibly resist occupation and not succumb to enemy propaganda”, sums up Magnus Hjort. But the world has moved on, and in recent years it has become clear that even in times of peace, information warfare is rife and that “dictatorships and authoritarian regimes use disinformation as a tool to achieve political, strategic and military,” says Hjort.

Officially inaugurated on May 10 in Kalmar, southeastern Sweden, the Swedish Psychological Defense Agency began work on January 1 and already has around 40 employees. Others should be recruited in the coming months, as the mission is vast. “We protect an open and democratic society and the free formation of opinions by identifying, analyzing and responding to inappropriate influences and other misleading information directed against Sweden or Swedish interests,” proclaims the institution’s website.

Specifically, the agency has four functions. First of all, it must ensure that society as a whole becomes aware of attempts to influence it, from foreign actors, state or otherwise. Secondly, it has an operational mission, consisting in detecting the disinformation campaigns carried out against Sweden. The agency also has a budget to finance research projects. Finally, it is responsible for supporting the media, by organizing training or offering them assistance if they find themselves at the heart of a destabilization campaign.

Preserve freedom of expression

Magnus Hjort is careful to point out that the agency does not intervene in the editorial or editorial content, nor does it take an interest in the misinformation circulating in Sweden: “This must be managed in the framework of an open debate between the political parties, or by the responsible government agencies, such as that of public health with regard to the pandemic, for example. The subject is extremely sensitive: it is about freedom of expression.

During its five months of existence, the Psychological Defense Agency has already had plenty to do. At the beginning of the year, a campaign, launched on social networks and which then materialized in the streets, caught his attention: Swedish social services were accused of “kidnapping” children from Muslim families to convert them. The agency quickly identified Islamist sites abroad suspected of fueling rumors and spreading false information. While it is difficult to establish the purpose of this campaign, “it may have been used to promote certain Islamist organizations abroad or advance pro-Islamist views in Sweden,” Hjort said.

Another phenomenon, which appeared on social media at the end of May, was the “Swedengate” – or how a message posted on Instagram set fire to the powder, claiming that Swedes did not feed their children’s friends when they came to play at home. Since then, the craziest claims have been circulating on the Web, including false information intended to present the kingdom as a nest of racists. In this case, the agency found no foreign influence. However, “that does not mean that a foreign power will not seize it, to exploit it and increase the polarization within Swedish society”, warns Hjort.