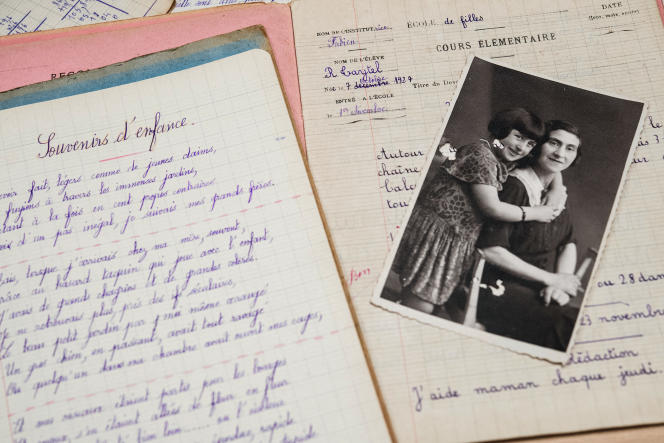

This June 16, in the classroom of the Jacques-Prévert college in Bourg-sur-Gironde, the emotion is palpable. On a table, photographs of Rachel Taytel and her parents have been placed, alongside her school certificate, obtained in Teuillac, near Bourg, on June 6, 1942. A binder carefully lists the ration cards of the family, greeting cards, birthday cards, official documents…

In the center of the room, a wicker trunk is presented. In turn, the 3rd graders of the Rachel-Taytel class present a school year of work around the story of the 16-year-old girl and her parents, deported in 1944 to Auschwitz. An important moment for these young people who are part of a special class whose ambition is to deepen the classic school program on the Second World War.

Santa’s hood

At the end of the ceremony, a man approaches. Alain Pons leans on his cane to reach the center of the room. “This trunk, which is now a century old, was for many years the basket of Father Christmas of Teuillac”, announces the man who was mayor from 1979 to 2001. In 1978, one of the inhabitants of the village must disguise as a bearded man dressed in red and white. But it lacks a hood.

A grandfather of a pupil from the municipal school, Gérard Juin, brings back a trunk found in his attic, which should do the trick. Residents add iron handles to it, and voila. But everyone ignores the past of this hood. It was not until 1985, when Alain Pons asked his constituents to search the attics and attics to unearth objects, as part of the preparation for the centenary of the school in the town.

Among these treasures, he was told school notebooks belonging to a young girl. On the first page, written in purple ink, is a name: Rachel Taytel. The one who has lived in Teuillac since 1955 is surprised to have never heard of this family, in a village of 600 inhabitants where everyone knows each other. Alain Pons discovers that these objects and school notebooks were in this trunk, which had been used for almost ten years as Santa’s basket.

The aedile begins to ask questions. “From there, I understood that we had found something special. I saw people cry and I looked at my population differently. All these people I had known forever had never spoken of the tragic fate of this family,” says Alain Pons.

The weight of guilt

The inhabitants relieve themselves of the weight of guilt for not having been able to protect their neighbors, the Taytels, sent to the death camp. “I realize that this story of France was also in my village, with painful traces,” he continues. Alain Pons takes hold of the story and begins his research.

As early as 1938, the French Republic, suspecting that war was ready to break out, inventoried vacant housing throughout the territory. The entire area of Villerupt, in Meurthe-et-Moselle, will be able to travel to the south-west of France, and 162 people arrive in Teuillac. The Taytel family, originally from Poland before settling in eastern France, decided to settle there.

They fill a wicker trunk with a few belongings, which will remain buried in Gérard Juin’s attic for almost forty years. The parents become agricultural workers, and Rachel Taytel, born in 1927, goes to the municipal school. At the request of the authorities, the city councilor of Teuillac then listed the Taytel as Jews. While the wave of arrests, ordered in 1942 by Maurice Papon, then secretary general of the Gironde prefecture, continued in the Bordeaux region, the whole family was arrested on January 12, 1944. Sent to Drancy, then to Auschwitz, it is directly gassed.

Such a long omerta

Telling the story of the Taytels always brings tears to Alain Pons. Since he discovered it, he has been trying to understand why the inhabitants of Teuillac have taken so many years to break the omerta. He learns that a Gypsy family, the Reinhards, inhabitants of Teuillac, has also been deported.

“Since then, I tell this story to all people who want to hear it, especially young people, children,” says Alain Pons. The history and geography teacher at Jacques-Prévert college, Jérôme Coussy, also took on the tragic fate of this family, with the English and French teachers. “The objective is to go further in history on the Jewish and Gypsy genocides”, explains Jérôme Coussy.

This June 16, the small ceremony ends with a buffet, where the young college students are active. “The history of the Second World War suddenly becomes more concrete, it took place a few kilometers from our home”, testify in chorus Charline and Oriane, who assimilate their teenage life to that of Rachel Taytel.

Next step, the organization of an exchange between the students of the Rachel-Taytel class and young people of the same age from a school in Tel Aviv. Alain Pons also offered Taytel family objects and documents to the Shoah Memorial in Paris. But before that, he wants to “label everything, explain it well”. Every element of the Taytel story has been part of his life for thirty-five years. Above all, parting with these snippets of lives would be a way of leaving Rachel behind. And this memory smuggler is not ready to say goodbye to him.