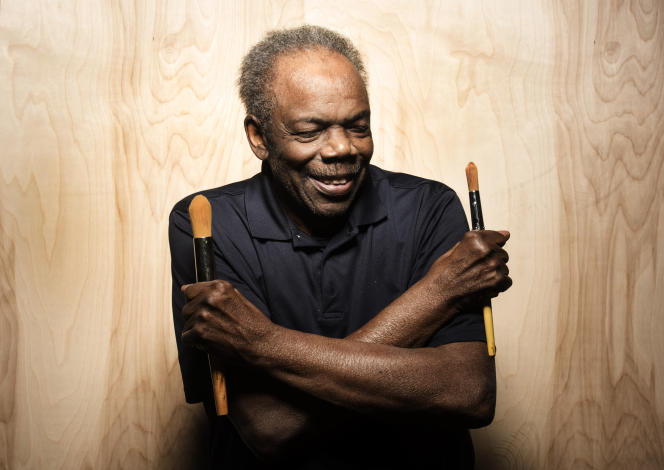

African-American painter Sam Gilliam died in Washington on June 25 at the age of 88. He was born in Tupelo (Mississippi) on November 30, 1933 in this deep South where blacks lived in terrible conditions aggravated by the Great Depression. Her father worked on the railroads and her mother took care of their eight children.

As a child, Sam Gilliam wanted to be a cartoonist and practiced in this direction. Graduated in 1951 from Central High School in Louisville (Kentucky), he entered the university of this city and obtained a first degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1955 – one of the first black students at this level in this university -, then the title of Master of Arts in 1961. In the meantime, he spent three years in the army.

Shortly after graduation, he left Louisville for Washington, having married Dorothy Butler, remembered in the history of the North American press as the first black female reporter hired by the Washington Post since its creation in 1877. He was then a young painter , caught like most of his contemporaries, in the flux of abstract expressionism and, like some, resolved to free himself from it. But he lived in Washington and not in New York and, in his city, then developed what is called the Washington Color School, with Morris Louis (1912-1962), Kenneth Noland (1924-2010) or Anne Truitt ( 1921-2004).

“Something Airy”

After a brief figurative period, Gilliam in turn tackles abstraction, not through geometry like Truitt or Noland, but by going beyond what Morris attempted. The abstraction according to Morris is made up of long undulating drips, each monochrome, which partially cover the white canvas and give an impression of movement. Gilliam decides to do without the frame, its straight edges and its angles and to work on free canvas which, carried by structures, suspended from the walls and ceilings, unfolds in stretched or folded surfaces: these are the Drapes , the sequel to which begins in 1965, and which remain his most famous works. Much later, in 2017, he spoke about it like this, not without self-mockery: “It was about finding something that I really like, something on a large scale, adapted to the dimensions of a wall (…), something aerial, no matter how, working in absence, just trying to build a shower curtain. »

In the execution as in the presentation, this “something of air” distinguishes itself from all that one can see then, whether it is the canvases of Rothko or Newman who have remained faithful to the rectangle or the creations of the minimalists, which exclude the idea of a partially random execution and do not call the spectator to circulate between waves of changing chromaticisms. Quickly, this unique way of painting and showing earned him exhibitions, commissions and growing recognition.

His new situation then allowed him to fight publicly against the avowed or unavowed segregation that governed the artistic world of his country. Thus, in 1971, he boycotted the invitation to exhibit from the Whitney Museum of American Art in solidarity with the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, which denounced the absence of any African-American critic among the experts consulted by the museum. The consequence of this righteous anger: in 1972, he was the first black artist invited to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale since the pavilion was created in 1930.

Different shades of black

Others would have stuck to the Drapes and exploited their success. From 1975, which is the year of the realization of the immense Seahorses for a facade of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gilliam deviates from it. He engages in the series of Black Paintings, which are arrangements of surfaces of different shades of black, whose texture and density vary. They are no longer floating canvases, but the frames are distinguished by their re-entrant angles and their discontinuities. Then come, from the 1980s, compositions that are increasingly difficult to describe, assemblies of colored planes cut into angular or curved surfaces, running on the walls like friezes whose elements are superimposed on the edges – bas-reliefs, so to speak.

Another solution for projecting colors into real space, developing rigid structures between or in front of the walls, carrying these same colored planes: these are the aluminum sculptures that Gilliam designed in 1986 for New York University or the metro Jamaica Center in 1991. Other works of this type were commissioned for Rutgers Law School in 2003, metro Washington in 2011 and, in 2016, for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

Several times exhibited in major North American museums, more rarely in Europe, it was to be the subject of a retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum in Sculpture Garden in Washington in 2020. Delayed due to the pandemic, it changed in May in presentation of his most recent works, because, in spite of an increasingly fragile health, Gilliam had not stopped working, always in and for color. Several of his works are currently presented in Paris by the Louis Vuitton Foundation in the exhibition “La Couleur en fugue”.