The discussion around the environmental effect of this Bitcoin mining ecosystem is heating up once more as professors have provided a fresh dose of perspective on the topic. Smith’s belief is that more nations will clamp down on Bitcoin mining as they use more electricity, given the increasing price of BTC is always matched by increasing hash rates.

While Coin Metrics creator Nic Carter has rebutted some of the factors raised in Smith’s column, there nevertheless seems to be divided opinion round the amount of energy which Bitcoin mining draws, the resources of the energy and the carbon footprint which the industry has on Earth.

The mining industry is arguably inclined to downplay the extent of its resource-intensive work, and some industry insiders have suggested that talk of Bitcoin’s environmental impact is a non-issue and that data indicates a large share of hash electricity draws energy from renewable sources. Nevertheless, environmental advocates have aimed their sights in the industry in return, and this has created a seemingly never-ending debate on the topic.

Cointelegraph has spoken with various academics in this region to gain an alternative perspective on the topic, by way of example, those behind the Cambridge Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, that has become a reliable point of reference for the estimated energy consumption of the Bitcoin network, albeit with some self-confessed limitations.

Furthermore, Aalborg University Ph.D. fellow Susanne Köhler and associate professor Massimo Pizzol co-authored a research titled”Life Cycle Assessment of Bitcoin Mining” that gives some data-driven assumptions about the environmental effects of the industry.

The CBECI was built to finally answer this query

In an interview with Cointelegraph, Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance crypto strength and blockchain lead Anton Dek unpacked the history of the CBEC and the methodology used to make the energy consumption estimates of its Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index.

The Cambridge research partner said the team had observed other versions which were seeking to create accurate estimates of their Bitcoin network’s energy usage had used a top notch approach, using data like the amount miners spend on electricity for instance.

The CBECI methodology is a”bottom-up approach” which uses data on the accessible mining hardware to make a lower and a upper bound estimate of their Bitcoin network’s energy intake. Dek clarified that the info is:”According to assumptions from goal figures like hash pace.” He further added:”These different machines have known efficiencies, joules of energy they expend to solve hashes. Based on these assumptions, we assembled the indicator .”

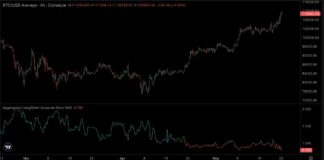

The index offers an estimated power consumption range, with its current theoretical lower bound annualized electricity consumption at 43.32 terawatt-hours into the theoretical upper bound in 476.18 TWh. The estimate of Bitcoin’s current intake is based on the assumption that miners use a mixture of hardware that is booming.

While the CBEC hasn’t made any models around the breakdown of the energy resources powering the Bitcoin system, the original intention for the invention of the CBECI index was to provide a carbon emission model. Dek explained that his team is working on that version, which he expects to see go live later this year.

Renewable-powered mining

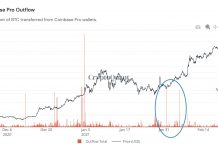

The CBECI website also gives a global mining map which essentially gives a breakdown of the way the Bitcoin mining system is distributed around the entire world. The map offers country-by-country hash prices, while China’s 12 provinces are also accounted for, provided that over half of the planet’s Bitcoin hash rate is located in the nation.

The breakdown of hash rate places is derived from data provided by mining pools BTC.com, Poolin and ViaBTC, which bring about 37% of the overall Bitcoin hash rate. Dek also noted that their information collection is currently over one year old but still allows researchers to make some precise assumptions about the energy sources used by miners in specific nations or regions.

“This is self-reported data by mining pools, therefore we must trust these guys. But even if it’s all true, we just cover 37% of Bitcoin’s total hash rate from those 3 pools which provided information to us. When we extrapolate it to the total miners, we assume that this is representativeness of this sample, which may not be accurate, provided that we’ve got more data from China. That is something we’re going to improve on.”

That regional perspective of China also gives a glimpse of the energy mix that miners are utilizing in various regions. The team has not released that specific data visualization nevertheless because it believes that the present 37% hash rate, that’s the basis of their information, is not representative enough to create accurate estimates of their network’s carbon footprint. Dek added:”If we examine the energy mix of each area, and then each nation, we will be able to assume the energy mix and then we’ll be able to more accurately gauge the carbon emission element.”

But, Dek explained that other researchers have arrived at estimates by taking the total annual power consumption of their Bitcoin network, approximately 130 terawatts-hour, and multiplying that by the average carbon emission factor (~0.5kilograms/carbon dioxide per kWh produced). The Cambridge research suggested that such an estimate may not be representative, given some assumptions Which Can Be drawn from regional location data of mining action:

“It’s more complicated than this since I feel the Bitcoin energy mix does not fall in the typical world combination. The main reason is that they utilize renewables, not because of their benevolence, but for purely economic factors. Hydropower exists in abundance in certain regions, and if you look on the Bitcoin mining map and China, the Sichuan region is still very significant for mining”

Dek pointed into the reported existence of mining facilities in the area that run on electricity produced by hydroelectric dams in Sichuan. The CBECI data also reflects the increase in the hash rate in the area during the rainy season, where excessive rains lead to an abundance of power generated by swollen dams. Based on him, Sichuan’s estimated share of global hash power:”In April (2020) it’s 9.66%, in September 2019 it was 37%.”

Perspectives from “Life Cycle Assessment of Bitcoin Mining”

It estimated the Bitcoin network absorbed 31.29 TWh using a carbon footprint of 17.29 metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2018 using data, information and methodology from previous studies on the topic.

In a dialogue with Cointelegraph, Köhler noted that their study indicates that the effects of new capacity being added to the Bitcoin mining network decreases according to two assumptions. The first is that gear becomes more efficient, which was proven to be true some two years later. The second premise — which miners would proceed to areas with more renewable energy resources — did not quite happen as anticipated:”Even though mining is more efficient, there is far more exploration done, and this usually means a bigger impact.” She added further:

“The assumptions in our study were influenced by rumors that China would crack down on their miners. More recent statistics on mining locations indicates that didn’t happen as expected. Still, the impact of enhancing the energy efficiency of the hardware means that the effect each added TH mined decreases (thus, in relative terms). However, we see now that the hash speed increases at a faster pace leading to larger overall consequences (consequently, in absolute terms) in other words.”

Since Köhler explainedtheir initial assumption was debunked to a certain extent, as the absolute growth of the Bitcoin system’s hash rate has contributed to higher electricity usage and, thus, more of an effect on the surroundings.

But , the Aalborg Ph.D. fellow admits that coming at an accurate estimate of the energy intake of the Bitcoin mining ecosystem as well as its own carbon footprint is a tall order. This is due to a number of factors, including the exact location and shares of miners, mining equipment used and the accuracy of data from several sources.

Incentives — the possibility of”green Bitcoin”

Another intriguing point raised by Dek is that his division has received from different players at the cryptocurrency market. Private firms and fund managers have enquired regarding services or data which can accurately establish how”green” a Bitcoin is, which depends upon whether or not it was mined using a renewable energy supply:

“Fund managers are now considering things such as’green Bitcoin.’ More institutional investors are coming from, and a lot of them are interested in the ESG (environmental, social and governance) consideration of Bitcoin. The perfect for them is to have a system which colors the Bitcoin.”

Dek also stated that some miners are searching for methods to demonstrate that they utilized green energy to mine their BTC. This could potentially create a market for”green Bitcoin” being marketed at a premium, which might motivate miners to switch to green energy sources. Meanwhile, Köhler considers that many miners are primarily concentrated on profit margins and cheap electricity, however It’s produced, will override the allure of green energy sources if they are not as affordable:

“There are some advantages to use renewable energies because in the case of hydropower in Sichuan which enables miners to utilize cheap electricity. However, it ought to be noted that this power is seasonal, so the availability isn’t the same throughout the year. In general, miners are incentivized to use the cheap power to maximize gains. By way of example, that also has electricity from coal from Inner Mongolia and electricity from petroleum in Iran.”

Dek shared these sentiments, saying that miners are typically rational about their business decisions. If there’s a cheaper energy source, they’re likely to use it regardless of how that energy is being created or what incentives are being offered to use green energy resources:”I find that miners, particularly large Bitcoin miners, are legitimate economic players. I think they’ll continue to act this way — if there’s a cheaper option, they will change, and otherwise, they’ll stay.”

Data is key

Since Köhler aptly summed up, more access to data from industry players may well supply the answers to some debate that is Very Likely to last for a Lot More years:”Better info and more transparency from the mining sector would allow for better models and less speculations — over the crypto space and in the General Public,” she added additional:

“Provided that the effects of Bitcoin mining continues to rise, I do not find an end to this argument.”

Dek agreed with the evaluation concerning the discussion on Bitcoin’s environmental effect due to the distributed nature of the network, even if more tools and data become available. He paints a stark reminder that Bitcoin’s protocol has been designed this way for a reason:”Bitcoin needs to be ineffective by design. When it’s very efficient, it would be very economical to do attacks on the network.”