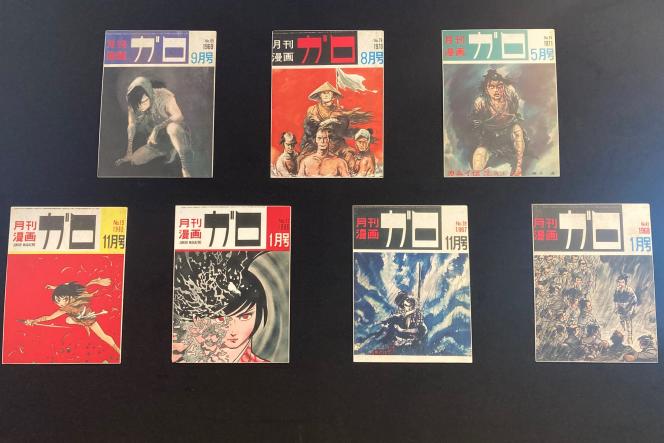

It is a monthly which has had considerable influence in the creation of manga, despite an almost artisanal production and a modest distribution (80,000 copies at the height of its popularity): the avant-garde Garo is honored in a free exhibition at the Maison de la culture du Japon, in Paris, until July 30, 2022.

This retrospective of the journal’s first ten years, from 1964 to 1974, based on the presentation of numerous original issues, competing titles and the artists who forged its reputation, had already been offered to the public in 2011 and 2013 by its curator, journalist and collector Claude Leblanc. However, it has the virtue of (re)discovering a monument of talent and audacity, at a time when manga is breaking sales records in France and when the generation of pioneering authors and pioneers of the beginnings of Garo s ‘off. Manga legend Shirato Sanpei, around whom the magazine was built, died in the fall of 2021, at the age of 89.

“The history of the magazine is part of a turning point in Japanese post-war history, that of reconstruction, the entry into economic growth and the upheavals of lifestyles, a period also of turmoil social and political,” summarizes Claude Leblanc. In a post-war Japan on its knees and reduced to misery, distractions are rare for the youth. Lending bookstores (kashihonya) and paper theater (kamishibai), which employs most current artists, are in decline. Magazines are booming.

Katsuichi Nagai and the cartoonist Shirato Sanpei then agree to create a magazine to host the mangaka’s new series and the one that will make him internationally famous: Kamui-Den, a martial story that takes place in the Edo period and tells in hollow the destiny of ordinary people, discrimination and social violence. However, the series was not ready for the launch of Garo in the summer of 1964 and appeared from number 4 until 1971, at the rate of a hundred pages per issue.

Narrative revolutions and political revolts

However, the magazine cannot rely on just one feather, however popular it may be. Garo therefore calls on other talents and promises them great freedom of tone, such as graphic latitudes and mutual aid. Second pillar of the magazine in its early days: Shigeru Mizuki, author of Kitaro Repelling Him, famous for his horrific stories and his representations of youkai (supernatural creatures typical of Japanese folklore), but also hailed for his works on war. Will follow Yoshiharu Tsuge and Yu Takita, pioneers of autobiographical comics, as well as Yoshihiro Tatsumi, inventor of the manga concept Gekiga (dramatic and mature story). With them, many other talents who will shape a manga freed, artistic, adult and sometimes dreamlike or parodic, often political and societal.

The magazine is anchored on the left, as evidenced by the forums of the “Meyasubako” section, created in March 1965. Informative chronicles of the subjects that cross Japanese society, these spaces will be used in particular by the team to stimulate the critical spirit of young people, to take a position in particular against the Vietnam War and, beyond that, to question themselves in a more philosophical way.

Because, although Garo was designed for a children’s audience – “on the first issues appears the subtitle ‘Junior magazine'”, specifies moreover Claude Leblanc -, the magazine will reach an older circle: students and young adults in a climate of protest and student revolts. “It cost 130 yen, then 150, which was much more expensive than other children’s magazines. Moreover, although with an educational ambition, Kamui-Den turns out to be a complex story “, which will resonate more readily with students by embodying a symbol of the fight against oppression, explains the exhibition curator.

An example for artists and readers

Garo’s reputation will grow in artistic, academic and intellectual circles. And inspire the mangakas published in major publishing houses, which themselves will expand their editorial offer for adults. This is the case, for example, of Shogakukan, which launched Big Comic in 1968 (Golgo 13, Quartier Lointain, etc.). Even Osamu Tezuka, father and star of modern manga, will seek, in the wake of Garo, to break into manga for adults by launching a rival publication, COM.

“Garo contributed to bringing out a reflection on the manga, its codes, its aesthetics. In 1966 appears Mangashugi, which could be translated as “mangaism”, the first manga critical review and whose number 1 is mainly devoted to the work of Yoshiharu Tsuge”, argues Claude Leblanc. It is also Garo’s talents that will appear at the end of the 1970s in the pages of Le Cri qui tue, a fleeting French-language magazine carried by Atoss Takemoto and offering manga in the country of Franco-Belgian comics. In 1987, the American comic book magazine Amazing Heroes gave pride of place to manga and a place of honor to Shirato Sanpei. First traces of the awakening of a curiosity of Western readers and publishers for Japanese comics, which will only grow.

Claude Leblanc epilogues his exhibition between 1971 and 1974, dates when Kamui-Den stops and when the first talents leave the ship. And the exhibition curator adds: “It is also from this moment that Katsuichi Nagai plans to end the magazine, wonders about the after Kamui-Den”, which was the reason for be from the review. Garo will eventually survive, with ups and downs, until 2002.