Aiming above all to elucidate and share sensory experience, Marie-Hélène Dumas takes some liberties with the biographical genre to restore the knowledge she has been able to accumulate about the artist, novelist and essayist Kate Millett (1934- 2017). It is also that she pursues here, beyond the individual destiny that she traces, a long-term investigation into the role of women in the history of the arts and of thought in the 20th century. After Lumières d’exil (Joëlle Losfeld, 2009), devoted to the photographer Germaine Krull (1897-1985), she has already given Libertalia editions, in 2019, a free biography of Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960), known for her suffragist engagement in early 20th century England.

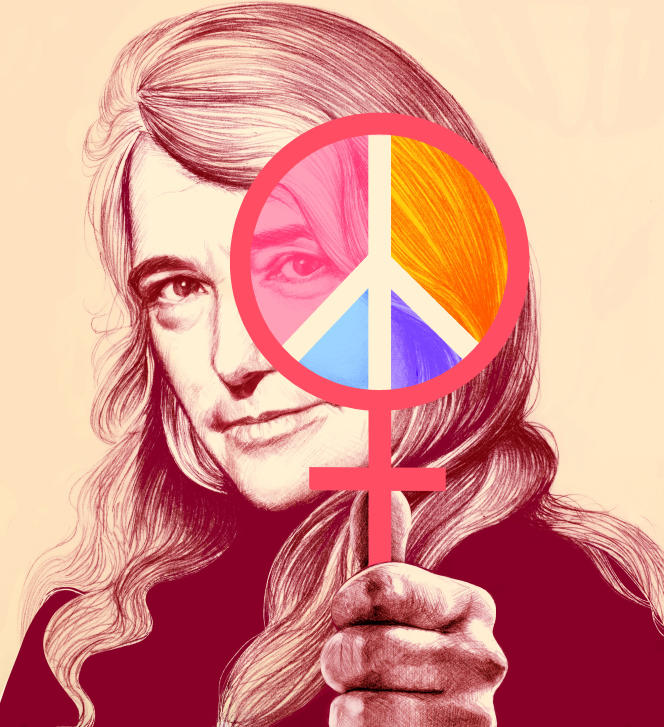

A major figure in the second wave of American feminism

Above all an artist, Kate Millett, whose life and work have embraced the convulsions of the various struggles for emancipation in America, from the 1960s to the “backlash”, this great reactionary reversal of the Reagan years, remains a major figure in the second wave of American feminism, alongside Betty Friedan or Angela Davis. In her very first essay, Sexual Politics, published in 1970 (La Politique dumale, Stock, 1971; reed. Des femmes-Antoinette Fouque, 2007), she analyzed patriarchal ideology in literature, tracking it down with biting lucidity in D. H. Lawrence or Norman Mailer, to contrast them with the work of Jean Genet, reading in the latter a “satire of the heterosexual code”, as his biographer sums it up here: “Virility and domination on one side, femininity, submission and hatred of oneself from the other. »

In France, it was above all her novels En vol (1974; Stock, 1975) and Sita (1977; Stock, 1978; rééd. Des femmes-Antoinette Fouque, 2008), both inspired by homosexual passions, which made her famous. , as well as In Iran (1979; Des femmes, 1981), in which she recounts her trip to Tehran after the 1979 revolution in an unsuccessful attempt to support a nascent feminist movement there. Kate Millett will have been in many other struggles, against racism, the Vietnam War and more than anything against confinement in all its forms, including psychiatric – it is not the least quality of this biography that of give the powerful desire to finally see translated into French The Loony-Bin Trip (“Chez les dingues”, 1990), “perhaps the most beautiful of his books”, in which Millett deals with the psychiatric universe, she who was twice hospitalized under duress and led a long fight to tear herself away from the lithium treatment imposed on her by the doctors, then her entourage, for fear that she would go off the rails again in the fever of struggles.

Emotion as a guide

From start to finish, Marie-Hélène Dumas favors emotion. She obviously remains attentive to the challenges of Millett’s feminist commitment, which materialized with the creation of the Women’s Art Colony Farm, a farm bought with her copyright to found a community of artists there with the help of her last companion, the photographer Sophie Keir. Still, Millett sometimes had trouble controlling her boat, in the ocean of feminist demands subject to contradictory currents and whirlpools. For example, when she was simultaneously rejected by some of the activists because of her lesbian love affairs and decried by others for having delayed claiming them – she remained married for more than twenty years to the Japanese artist Fumio Yoshimura .

Always, emotion will have guided his engagements, not the other way around; it is by pursuing them that, allowing himself jumps in time, his biographer manages to restore the fights of Kate Millett by sparing the reader any nostalgic feeling: in these 1970s which could pass for a golden age, the refusing subpoenas was no less trying, heartbreaking than it can be today. Bertrand Leclair