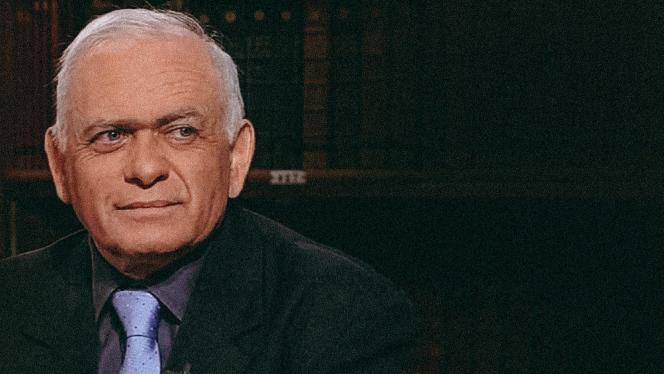

After the dark introductory monologue of the director, the blue and penetrating gaze of a sexagenarian captures the attention. Alone in front of the camera, Michaël Bar-Zvi presents himself as a “philosopher and writer”, modestly, like a Mensch – in Yiddish, someone attentive and honest. We are then in the middle of filming La Richesse (broadcast in 2019), a documentary by Elisabeth Lenchener devoted to the delicate relationship between man and money.

The death of Michaël Bar-Zvi on May 29, 2018, at the age of 68, will convince the director to tackle a subject more divisive than money – Zionism -, by devoting a portrait to his friend from thirty years. It is broadcast on the anniversary of the creation of the State of Israel, May 14, 1948, in order to “make Zionism more accessible, break down prejudices and elevate the debate”, Elisabeth Lenchener told Le Monde , Monday, May 9.

The ambitious goal requires intellectual effort, including on the part of the viewer. This one should lend itself willingly, carried by Michaël Bar-Zvi, “a complex, interesting, fascinating character and a great intellectual”, according to Daniel Shek, Israeli ambassador to France from 2006 to 2010.

fighting spirit

The refusal of simplification and combativeness appear in each of his interventions. Since the evocation of his alya (return to Israel for a Jew), at 25, “in a completely different spirit than what we hear today [but] to bring my love of France to Israel”, until ‘to his development, in front of the journalist Michael Grynszpan in 2016, on his double intellectual filiation: with Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995) and the “more sulphurous” Pierre Boutang (1916-1998). The professor thus recalls that the latter was his philosophy teacher at Lycée Turgot in 1967 and that the teacher was no longer “anti-Semitic but philo-Semitic, Zionist and very committed to Israel”.

Later, he defended his Eloge de la guerre après la Shoah (Hermann, 2010) with the same pedagogy against Jean-Pierre Elkabbach, on March 26, 2010. On the set of i24 again, he mastered his criticisms after the broadcast on M6 of an issue of “Exclusive Investigation” on Jerusalem, December 18, 2016.

The confrontation of ideas is a driving force. “Michel [Michaël Bar-Zvi] had something eminently chivalrous, crossing words and concepts as one crosses swords”, recalls Arthur Cohen, from Hermann editions.

Another engine, the family. His father, a musician, who believed that the Holocaust did not belong to “memory” but to Evil. Anat Bar-Zvi, his widow and mother of his three children, delivers a sweet testimony of their life together. “I think this marriage will bring peace,” he said on a home video on their wedding day.

Since the 2000s, Michaël Bar-Zvi pointed to new dangers, such as anti-Zionism, “permission to be democratically anti-Semitic”, said Vladimir Jankélévitch, and “the Islamo-leftist Palestinian discourse”, an ideology “dominant in universities and in intellectual circles in France”.

“Yes, I will defend the sand of Israel,/The land of Israel, the children of Israel;/Let’s die for the sand of Israel,/The land of Israel, the children of Israel,” sings Serge Gainsbourg, in Le Sable et le Soldat, written in 1967, which opens this portrait. And little broadcast since.