Is there a good way for a journalist to announce to his management that he “falsified the number one world event”? Probably not. Even if the hero of Our correspondent on the spot, with the sense of derision that characterizes him, must recognize it: in an article as in a conversation, it would be “a fucking introduction”. For Robert Perisic’s novel, it is at the very least a devilishly effective narrative and comic spring. The culpable negligence shown by Tin, a young economics editor with the well-considered look of an old rocker, leaves him no choice. His cousin, whom he recommended as a reporter to cover the beginnings of the war in Iraq in 2003, quickly revealed his inability to fulfill his task. He has to rewrite, neither seen nor known, the meaningless texts that this ex-soldier traumatized by the Balkan war sends him. Which triggers, when he disappears, a series of disasters from which it is hard to see how Tin could emerge from the top.

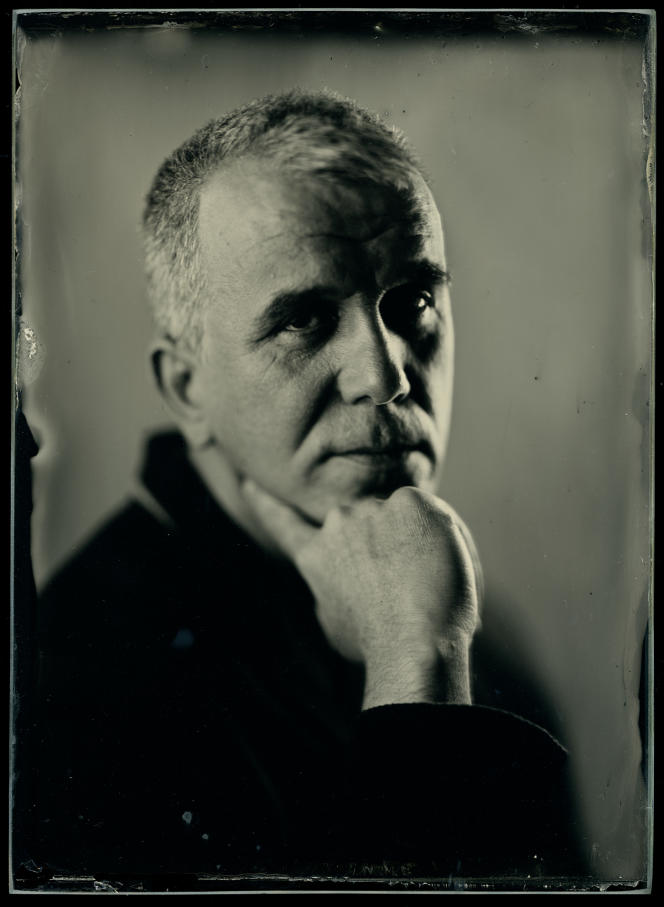

But the tragicomic fate that befalls the character is above all a way, for the Croatian writer, born in 1969, to make clear the difficulty his generation had in finding its place, after the decades of socialism under Tito and of war in the former Yugoslavia. Published in Croatia in 2007, where it was immediately hailed as a great generational novel, the book has lost none of its acidity when we discover it, fifteen years later, in its French translation.

Don’t make waves

In a society in full apprenticeship of democracy and capitalism (Croatia then emerged from the gripping reign of Franjo Tudjman, and turned towards Europe), no one “knew how to live anymore, writes the novelist. No one knows anymore if his life is the right one… Or if it should be turned upside down. To exercise a profession without passion, to be able to buy an apartment on credit. Don’t make waves. Investing your savings in the stock market, believing yourself to be smarter than everyone else, at the risk of losing everything. To flee at all costs the model of his elders, to take advantage of the economic and political freedom which they had always lacked. Dare to live according to your desires, even if it means feeling marginalized: “All this freedom of choice creates uncertainty”, Perisic has his character say.

And the latter adds: “I was not exactly used to clear horizons. (…) There had been communism, then the war, then the dictatorship… An eternal stuffing of slack. He must face the facts about the reasons for his unease in a democratic regime: “It’s because now I’m supposed to be a subject!” Too late to put the blame on someone (…). In truth, I’m supposed to take responsibility. Act, choose. “Hard to believe, when the world around you seems more like a theater, where everyone dons costume and social role. Substituting novelty for creativity, and fame for talent.

A skepticism that is more disillusioned than truly reproachful

In a style that is both clear and lively, fatalistic but saved from despair by the constant irony he demonstrates, Robert Perisic paints a striking and endearing picture of a society in full mutation, whose flaws never reveal themselves so well. only when they are artificially filled. It also holds up to the old liberal democracies a barely magnifying mirror in which the tensions that run through them are reflected without them even being surprised. And opposes to the heralds of uninhibited capitalism in which Croatia engages headlong with a skepticism that is more disillusioned than truly reproachful.

In a few decisive days, Tin’s professional, social and private lives take an apocalyptic turn. But the tenderness that the novelist obviously feels for his antihero, and that he knows how to share with the reader, quickly suggests that this novel of “unlearning” remains indeed an initiatory journey. Where the fact of “falling from [his] throne”, from the world which he thought it “belonged to him”, is, for the character, the necessary beginnings of a free and rich life, the value of which has no meaning. nothing much to do with stock market fluctuations.