On July 17, 1942, Heinrich Himmler witnessed the murder of a group of Dutch Jews in the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center. The gas chambers have been operating since March. The head of the SS came to make sure they were doing their job, as the “final solution to the Jewish question”, according to Nazi terminology, entered its “industrial” phase at the beginning of the year, underlines Laurent Joly, who recalls the scene in a passage from his new book, La Rafle du Vel d’Hiv. He adds that, in the face of the massacre, Himmler remained “silent” but that, in the evening, at dinner, “he seemed transported with happiness”.

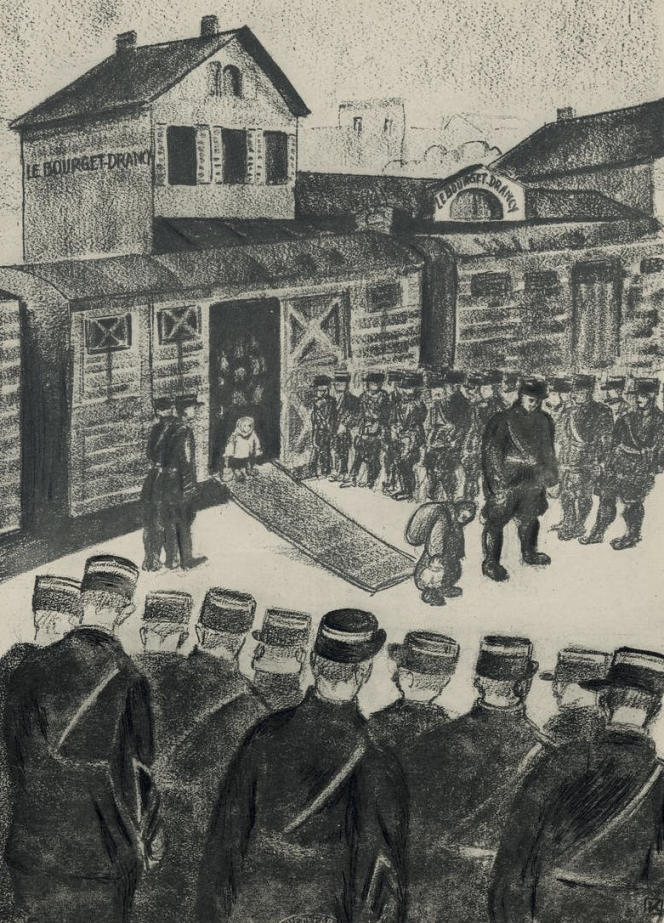

The same day, in Paris, Jankiel Belefer, 15 and a half, was locked up in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, in the 15th arrondissement, with thousands of other foreign Jews arrested like him, since the day before, by the French police. The next day, he wrote to his best friend: “I don’t think we’ll see each other again and you see I think it’s really the end. In a few days, he will be taken to one of the Loiret internment camps, from where he will be deported to Auschwitz. A total of 12,884 people were arrested on July 16 and 17; 4,900 were taken to the Drancy camp; 8,000 at Vel d’Hiv. “Only a few hundred will survive,” notes the historian.

The climax of the Vichy regime’s policy of collaboration

A decisive step in the Nazi plan to destroy the Jews of France, the climax of the Vichy regime’s policy of collaboration with the occupier, “the Vel d’Hiv roundup is the most important operation implemented in Western Europe in as part of the “Final Solution”. The impressive mass of unpublished documents exploited by Laurent Joly is however enough to show the extent of what we still had to learn. The essentials, namely the extent of the crime and the involvement of the French authorities, were certainly known after the war, thanks to articles by Georges Wellers in the review Le Monde jew, or, in 1967, to the book La Grande Rafle du Vel d’Hiv, by Claude Lévy and Paul Tillard (Robert Laffont). But the resulting picture turns out to be both fragmented and tainted with errors, reproduced in the meantime in the books, moreover fundamental, of the greatest historians of the Holocaust and collaboration, the Americans Raul Hilberg and Robert Paxton or the Israeli Saul Friedländer.

So the roundup never had the widespread name “Spring Wind”. Similarly, activists from the French People’s Party, Jacques Doriot’s collaborationist movement, did not take part in the roundup. Nor were there a hundred suicides among the victims. The balance sheet itself, if it has long been known for July 16 and 17, is here the subject of a significant reassessment. This is also one of the decisive contributions of the book, which brings to light a “roundup after the roundup”. Two-thirds of the people targeted by an “arrest card” having escaped the roundup on July 17, the authorities immediately decided to continue the operation. By August 31, an additional 1,200 adults had been arrested, and hundreds of children – records, to date, do not provide an exact figure. That is a real toll of more than 14,000 victims, not counting subsequent raids.

Hear the voices of victims

Beyond these facts, finally restored with rigor, and in reality thanks to the obstinate precision with which the author of The State against the Jews (Grasset, 2018) establishes them, the vision of events acquires a finesse and depth. unmatched. The administrative and police archives allow us to observe more closely the mixture of anti-Semitism, cowardice and opportunism which presided over the decisions of the French authorities. Delivering the maximum number of victims to the Germans was to give the Vichy regime room for negotiation, and thereby increased power. Thus, while the principle of delivering only foreign Jews had been fixed from the outset, French officials decided to deport some 3,000 French people under the age of 15, children of foreigners, to increase the toll and be in a position of force in this political game of which Laurent Joly shows, with more acuity than ever, the cruelty and the cynicism.

His book, however, would not have this breadth if it had not, to the extent that it does, given voice to the victims. Newspapers, letters, retrospective testimonies form a constant counterpoint to the political horror that was first to be told but which only takes on its full weight when faced with this intimate reality of genocidal devastation. Anguish and distress, survival and dread, almost always death: any story at this level is ultimately the story of individuals, carried away by events. The Rafle du Vel d’Hiv is a masterful development, long overdue. But it is also, at a time when the last witnesses are disappearing, a memorial, the exact and intimate record of what the Shoah was in France, as the French implemented it.

Read an extract on the Grasset editions website.