Ugur Üngör is a professor at the University of Amsterdam, specialist in genocide and mass violence, researcher at the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD). He is the author of Paramilitarism. Mass Violence in the Shadow of the State (“paramilitarism, mass violence in the shadow of the State”; Oxford University Press, 2020, untranslated) and, in May, with Jaber Baker, De Syrische goelag. De gevangenissen van Assad, 1970-2020 (“The Syrian Gulag, Assad’s Prisons”; Boom Publishers Amsterdam, untranslated). His next book on the shabiha, these armed gangs in the pay of the Damascus regime, will appear in 2023: Assad’s Militias and Mass Violence in Syria (Cambridge University Press).

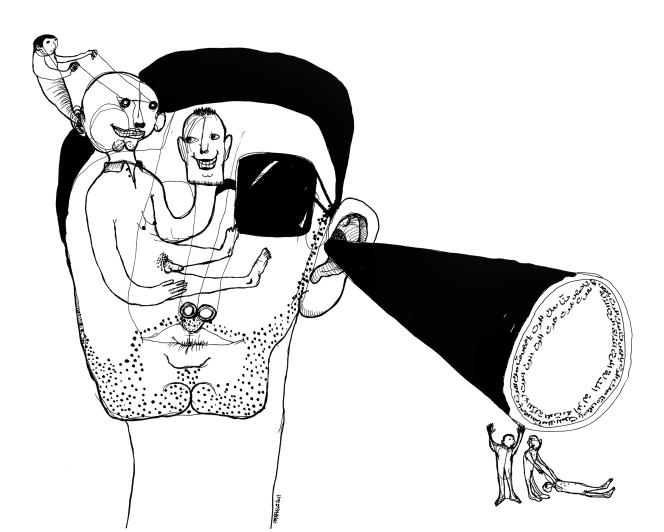

The chabiha have no flag, uniforms or hierarchical structure and their relationship with power is informal. In fact, anyone who does not belong to the army, the mukhabarat [intelligence services], the police or the special forces, but carries arms in the name of [President Bashar Al-]Assad, can be called “shabiha”. They have infiltrated local authorities, run organized crime networks and use state protection to extend their control and terrorize. Until the March 2011 uprising, the shabiha mainly referred to Alawites [members of a long-repressed sect, lately rallied to Shiism, to which the Assads claim to belong] in the stronghold of the Assad family [on the coast, between Tartous and Latakia , and in the mountainous hinterland]. This qualifier was then extended to any armed man, in civilian clothes, who attacked the demonstrators.

It is not an academic term, but a word from the Syrian Arabic dialect – close to chabaha, which means “ghost” – which appeared after the coup d’etat of Hafez Al-Assad [father of the current president], in 1970. He then designated the militias under the orders [of his brother and rival Jamil Al-Assad, then under those] of the clan, in general. The Syrians identified them by their black Mercedes with tinted windows [Shabah model, another explanation given for their name], which caused panic.

From 1975, the year of the outbreak of the civil war in neighboring Lebanon, and with the entry of Syrian troops into this country [in 1976], smuggling flourished from the Lebanese coast, [in places held by pro-Syrian Lebanese Christian militias] from the port of Beirut. The army encouraged trafficking of all kinds, in exchange for a heavy percentage levied on the goods then resold on the Syrian market. These resources began to dry up in 1990, when peace returned to Lebanon. The chabiha then began to engage in infighting, as I was told by residents of Latakia: they eliminated each other, in a spiral of vendettas. It took the intervention of Hafez Al-Assad to put an end to it. After the latter’s death in 2000, Bashar Al-Assad’s first decade in power was characterized by economic liberalization which, more than ever, placed the shabiha above the law.

They were there, and they were ready. They beat and chased the protesters, in coordination with the mukhabarat. One of the chabiha I interviewed as part of my research told me that every Friday, a traditional day of demonstrations, he closed his shop and went to repress the protesters – as if he were going to ordinary occupation. Back home, he was cleaning his bloody clothes… His mother was telling him to stop, not because it was morally wrong, but because it was risky! He continued to do so, every Friday, for a year. The chabiha no longer just beat, they stopped and loaded people into the trunks of their cars to deliver them to the intelligence services.

Then they started shooting at the demonstrators. Subsequently, they took part in massacres, such as that of Houla, on May 25, 2012 [at least 108 dead, including 34 women and 49 children, according to the UN], near Homs. In this region, between 2012 and 2013, human rights organizations documented many atrocities perpetrated by the chabiha: gang rapes, kidnappings, torture, summary executions, mass killings…

It is implicit. Taking up a weapon and committing violence in support of the regime is unofficially permitted. The chabiha enjoy total impunity. The regime knows what these men are doing and allows it; these men know that the regime allows them to do so. As in a kind of choreography, it is not necessary to verbalize it. These militias constitute a shadow state, but without a formal hierarchy, they cannot be officially attached to the regime. He can therefore resort to what is called “plausible deniability”. This is what he did, in 2012, when a United Nations commission of inquiry denounced that “government forces [acted] in concert with the Chabiha militias”. The reaction of the regime was first to laugh, then to deny, and finally to claim to be itself a victim of terrorism… For their part, the chabiha deny that the regime structured, armed and financed them.

During my research, when I asked the authorities. They replied: “There is no shabiha in our country, but ‘Defense Forces'”, adding that “everyone in Syria is defending the country”… Countering this denial is complex, because this militia is very diverse. It is not a single, structured group. The shabihas of Aleppo have developed through business networks, while in Homs or Damascus, ethnic and religious ties have prevailed. Sakr Rustom, an engineer by profession, was for example a complete stranger before the 2011 uprising: he became all-powerful at the head of the chabiha of Homs under the impetus of his maternal uncle, General Bassam Hassan, in direct connection with the Assad clan.

In Aleppo, which is predominantly Sunni, it happened differently. A few prominent families in this city had a seat in parliament as representatives of the [single ruling] Baath Party; they turned their tribes into mercenaries for a handful of dollars a week. The shabiha of Aleppo worked under the leadership of air force intelligence, whose local leader was Adib Salameh [until his promotion in 2016]. There are thus photos showing the latter in the company of the boss of the shabiha of Aleppo [Hassan Zeino Berri], executed on August 1, 2012 with other members of his clan by the Free Syrian Army [ASL, armed opposition].

If there were, they were demoted or even eliminated. This is what happened to Assef Shawkat, husband of Bashar Al-Assad’s sister, who was demoted to deputy defense minister after being head of military intelligence. He was assassinated on July 12, 2012, during a suicide attack, in the middle of a meeting in Damascus [in the ultra-protected building of National Security, where also the Minister of Defense Daoud Rajha died]. No one could come with a bomb to a place like this – unless it was an inside job: the hardliners got rid of those who got in their way. In addition, the Alawites who supported the regime while refusing to become chabiha were marginalized. If their villages were attacked by the FSA, the regime left them to fend for themselves.

Their task was first to hold the territory, to patrol and to erect roadblocks. In 2012, soldiers from the national army defected en masse. Some of them joined the ASL [armed opposition], others the Islamist groups. Threatened, the regime needed an armed rear base. Tehran then advised the regime in Damascus to merge the shabiha into a single body, dubbed the “National Defense Forces” [NDF]. The groups scattered over the territory have been organized, paid, trained. They received equipment and became a strike force, more than a force of repression. Iran wanted to reproduce in Syria the model of its bassidji [paramilitary branch of the guards of the Islamic revolution]. That is to say, men without tanks or heavy weapons, but in uniform and with muscles! Many shabiha traveled to Iran by bus or plane, where they received training before returning.

These training sessions are the result of an agreement between Ali Mamlouk, former right-hand man of Hafez Al-Assad and head of the mukhabarat [under international arrest warrant in several countries, for “complicity in acts of torture, complicity in enforced disappearances, complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes and war crimes”], and Iranian officers. An Iranian general recounted it in his Memoirs. I myself heard the story of men who had been trained in Iran. But this kind of decision taken at the top is very opaque and no one at this level has defected, to my knowledge, to give the details. As a historian, I can’t just go to Tehran and ask, “Can I see your archives?” One can only understand that the Iranians wanted to keep the Syrian regime in place and that they also hoped to penetrate Syrian society. These agreements have also enabled them to get closer geographically to Israel, their great enemy. From now on, they no longer operate only from Lebanon, but also from Syria.

In 2013, many of their members died because they were sent to fight on the front lines, because they held roadblocks and were targeted by the Free Syrian Army, but also by jihadist groups. At that point, many decided to quit. As long as they were the bosses in Damascus, criss-crossing civilian neighborhoods in their big cars with tinted windows and carrying guns, they were fine. But when they had to fight against the Al-Nusra Front [which appeared in Syria in 2012 and affiliated with Al-Qaida in 2013], a good part gave up. “Those crazy Islamists would have cut my head off! one of them told me.

In September 2015, the military intervention of Moscow – the other support of the regime of Bashar Al-Assad – in Syria was accompanied by a new organization. The Russians were not followers of the Iranian business model and they opposed the duplication of bassidji. For Moscow, any armed man had to join the army. Thus was born the 5th corps [also called “5th legion”], in which were integrated the NDF, which Russia, in turn, trained and armed.

As for the “retired” militiamen, while most remained in Syria, some also slipped in among the refugees who reached Europe in 2015 and 2016. It is quite striking to see how much the chabiha underestimate the trauma they caused. The Syrians certainly expected the mukhabarat to torture or kill them, but not that relatives – sometimes friends – would turn into executioners! In Europe, their victims have opened websites to gather information about their account. Syrian NGOs and activists document their presence in Europe, spotted in particular thanks to the profiles posted by these men on social networks. There is a site that traces the former militiamen in Sweden, France, Belgium, Germany, Austria… In Syria, the chabiha posted selfies, weapons in hand, to show that they were the kings of the neighborhood. Now they take pictures of themselves eating a kebab, in Berlin or elsewhere.

Chabiha are flexible “workers”. They were very useful in 2011 in suppressing protesters. Some are now “retired”, others were able to write informal reports for the regime on the activities of the opposition in exile. But, in general, this mission is devolved to the intelligence services. And then, a chabiha who leaves the country can be considered a traitor. In the cases I have studied, there is that of a man from Salamiye, in the province of Hama. He was in charge of a checkpoint in this city and killed people there. One day, he decided to take refuge in Europe. He passed through Turkey, Greece and followed the route of the Balkan route. Arrived in Belgium, he was recognized by other Syrians, who reported his presence to the police. The man quickly left for Syria: upon his arrival, the regime arrested him for espionage and imprisoned him for two months.

They have no qualifications, no diplomas. As a result, they have often joined gangs, organized crime, or engage in petty crime. In 2011, in Syria, it was out of the question for someone who had a good job, or a diploma, to join the shabiha.

For the first time, an intelligence officer was put on trial. It is enormous ! And it wasn’t just anyone: it was a colonel, head of the Department of State Security. Before the revolution, he evolved in Syrian society with incredible privileges and power. At Division 251, the regime was torturing people long before 2011. The Syrian intelligence services are, fundamentally, a criminal organization. That a leader of this criminal organization had to face justice is absolutely unique, because impunity for these individuals has been the norm for fifty years. They can arrest anyone, kill anyone, without anyone having a say. During his trial, Anwar Raslan presented himself as a sort of volunteer resistance fighter, because he allegedly helped people… The commander of the [Nazi extermination] camp in Treblinka, Franz Stangl, said exactly the same thing and claimed to be innocent! If one prisoner out of 4,000 is offered coffee, what about the other 3,999, hung from the ceiling and electrocuted? These men are so conditioned by the system of violence that they don’t even see the problem! In such regimes, even the most “moderate” are not innocent.

No one can predict the future, but I believe it will be very difficult to demonstrate the links between the militias and Bashar Al-Assad’s regime. Even when we know who the direct perpetrators of crimes are, there are no paper trails and Damascus retains control of forensic evidence in the country. No one can go to Syria today to investigate the mass graves, to take DNA samples and determine that these civilians were killed with Syrian army bullets. The only solution is the collective memory of the Syrian people. He knows, street after street, which is a chabiha and who did what. We need an ad hoc tribunal, but the will, at the international level, is not there. Syria has powerful support and benefits from Russia’s systematic vetoes of any UN draft resolution, including referral to the International Criminal Court. As long as Vladimir Putin is in power, he will not allow this to happen.

Thanks to universal jurisdiction, in France or Germany, mukhabarat officials can be sentenced, as in Koblenz. But I am very pessimistic. The chabiha will get away with it, for lack of sufficient evidence. One of them had been identified by other Syrians in a refugee camp in the Netherlands. There was an investigation, but judges in a court in The Hague eventually dismissed the case because the suspect didn’t have enough stripes on his epaulette! This is exactly why the chabiha exist: they cannot be officially tied to the regime. And those who could will not speak. The intelligence bosses know who committed the crimes and where the mass graves are, but in their basements there are still thousands of people being tortured. Until the mukhabarat are dismantled, there will be no serious transition in Syria. You can’t abolish the government but keep the Gestapo! It can’t work.

The idea that it all came from the Nazis is quite sensationalist. If we look for comparisons, we can just as well bring the Assad regime closer to the Pinochet, Suharto, Stasi, KGB dictatorships… I believe, unfortunately, that the masters of Damascus do not need anyone to build their regime . There are also internal historical precedents that inspired the construction of this dictatorship. The French colonial period [from 1920 to 1946, Syria was under French mandate] was not democratic and, before that, there was the Ottoman Empire. What is the democratic tradition in this country?