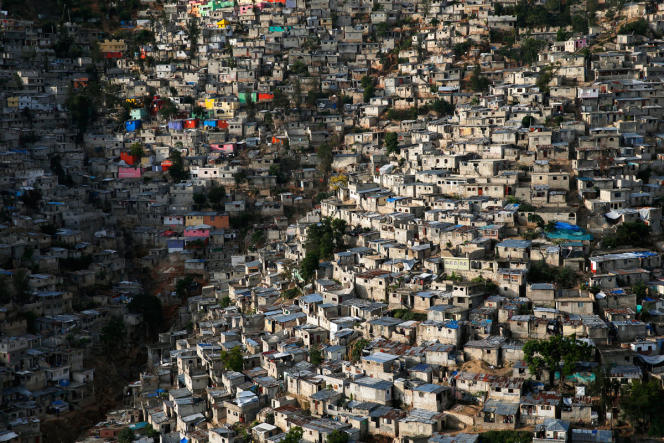

On January 1, 1804, Haitians declared their independence following a slave revolt against French settlers. Two centuries later, Haiti is one of the poorest countries on the planet. A situation often blamed on a failing state and endemic corruption. The persistent misery it endures is, however, largely the result of outside intervention. This is the conclusion of an investigation (also available in French) conducted for thirteen months by journalists from the New York Times.

Through a series of five articles, published on May 20, the American newspaper traces the history of Haitian debt, reveals in detail who has benefited from it and explains how it continues to affect the country. With, as a backdrop, this question: what if the country had not been plundered since its birth by foreign powers and by its own leaders?

In 1825, twenty-one years after its independence, Haiti saw a French ship – followed by a war flotilla – drop anchor in the port of Port-au-Prince, its capital. An emissary from King Charles X issues an ultimatum: pay reparations to France or war will be declared. Without a real ally, the small country has little choice. He will pay the sum demanded – 150 million francs, to be paid in five annual installments. “The amount far exceeds the meager means of Haiti”, underlines the New York Times. In addition, France forces its former colony to borrow from French banks to settle its first payment. Interest is added to the initial sum. This is what historians call the “double debt”. Questioned by the newspaper, the French economist Thomas Piketty speaks of “neocolonialism through debt”.

The New York daily assesses the total amount of sums paid at 560 million dollars in present value (525 million euros). But for each franc paid to the old masters corresponds so much money that is not invested to guarantee the prosperity of the nation. “Payments to France cost Haiti between $21 billion and $115 billion [€20 billion to €108 billion] in lost economic growth,” concludes the New York Times investigation, which refers to “a spiral of indebtedness that crippled the country for more than a century”.

In 1880, France changed tactics. The National Bank of Haiti is created, but it is only Haitian in name. The American daily details:

“Controlled by a board of directors based in Paris, it was founded (…) by a French bank, Crédit Industriel et Commercial, or CIC, and generates staggering profits for its shareholders in France. The CIC controls Haiti’s public treasury – the government cannot deposit or withdraw funds without paying commissions. »

Archives found by the New York Times show that the CIC siphoned tens of millions of francs from Haiti for the benefit of French investors and burdened its governments with successive loans.

CIC and its parent company, the Banque Fédérative du Crédit Mutuel (BFCM), reacted on Monday, May 23, recalling that it had “acquired Crédit Industriel et Commercial, then a bank owned by the French State, at the dawn of the 21st century. century, in 1998”. “Because it is important to illuminate all components of the history of colonization – including in the 1870s, the mutual bank will fund independent academic work to shed light on this past,” adds the CIC in a communicated.

In 1910, new shareholders took over the National Bank of Haiti. They are French, German and American. Again, the country’s national bank is entirely in foreign hands. It grants a new loan to the Haitian government, on draconian conditions. Thus, in 1911, out of three dollars collected through the tax on coffee, the country’s main source of income, 2.53 dollars were used to repay sums borrowed from French investors.

The French are concerned about the growing hold of the Americans on the shareholding of the national bank. They’re right. The interest of the United States marks, in reality, the beginning of the American campaign to oust the French and the Germans from Haiti.

In December 1914, a small group of Marines broke into the National Bank and seized 500,000 dollars (469,000 euros) in gold. A few days later, the loot is stored in a bank on Wall Street. This operation foreshadowed a much larger takeover: in the summer of 1915, American soldiers invaded Haiti. Washington claims that the country is too poor and too unstable to be left to its own devices. Then begins a military occupation that will last nineteen years.

Under pressure, in particular, from the National City Bank (the ancestor of Citigroup), Washington takes control of Haiti – Parliament is dissolved, a new Constitution is drafted, a puppet government is put in place – and of its finances. . According to information collected by the New York Times, in ten years, “a quarter of Haiti’s total income has gone to repaying debts controlled by the National City Bank”. In addition, American soldiers resorted to forced labor and did not hesitate to shoot fugitives. For many Haitians, it is a return to slavery.

Faced with the anger of the inhabitants and international indignation, the United States ended up resigning itself to a withdrawal. In 1934, the last American troops left the country. The United States will maintain its financial control for another thirteen years, until Haiti finishes repaying its debts to Wall Street.

If it does not explain everything, the corruption of Haitian leaders has only accentuated the misery of the country. In fact, notes the New York Times, this is a problem that goes back a long way:

“In granting the 1875 loan, the French bankers immediately took 40% of its total amount. The balance was mainly used to pay off other debts, and a small part disappeared into the pockets of crooked Haitian officials. »

In 1957, Haitians elected a doctor, François Duvalier, as president. The latter is also supported by Washington. At that time, and for the first time in one hundred and thirty years, Haiti no longer had to bear the burden of a crushing international debt. But, for thirty years, the country will suffer the brutal dictatorship of “Papa Doc” and then his son who will embezzle millions of dollars.

Added to this are the many natural disasters that have devastated the country in its recent history: the deadly earthquake of 2010, the one that occurred in 2021, Hurricane Gordon in 1994, Jeanne in 2004, Matthew in 2016…

The affair of the “double debt” is a hidden episode, at least little known, in the history of France. On April 7, 2003, the Haitian President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, gave a speech that had the effect of an explosion: he asked France to reimburse the sum paid by his country, which he quantified very precisely at 21 685,135,571 dollars and 48 cents. French diplomats choke and mock this amount which they consider delusional. Nevertheless, a New York Times economic analysis reveals that “the long-term losses caused by Haiti’s remittances to France could be surprisingly close to the figure put forward by Mr. Aristide. The estimate of the Haitian president may even have been modest. »

In 2004, Mr. Aristide was ousted from power and left Haiti, following an operation orchestrated by France and the United States. Paris and Washington “have always said that his ouster had nothing to do with the demand for restitution, blaming instead the autocratic turn of the Haitian president and his loss of control of the country”, recalls the New York Times. But Thierry Burkard, French ambassador to Port-au-Prince in 2004, admitted to the newspaper that the two countries did orchestrate “a coup” against Mr. Aristide. As for the connection between his ousting and the restitution claim, Mr. Burkard acknowledges that “that’s probably a bit of that too.” The daily then explains that by asking for restitution, Haiti “risked encouraging other countries in the Caribbean and Africa to follow its example”.