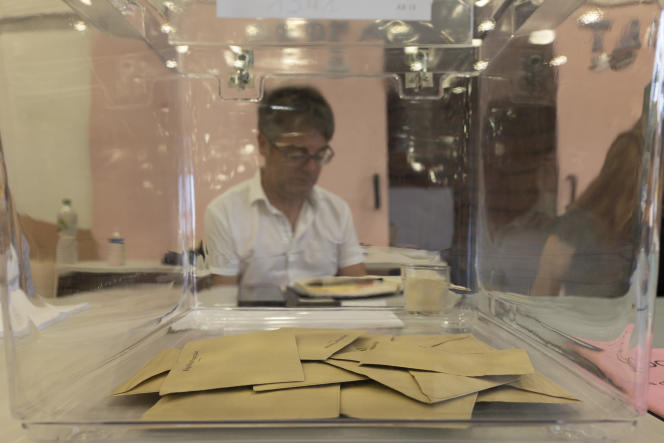

The second round of the 2022 legislative elections was, unsurprisingly, marked by low participation (46.23% of registered voters). This confirms a strong trend observable in recent years, namely the acceleration, since the accession of Emmanuel Macron to power, of the abstentionist cycle set in motion towards the end of the Glorious Thirty and concerning all elections, local and national.

Legislative elections have become second-tier elections. Their scope has been hampered by the presidentialization of our political system, which reduces the National Assembly to a mere registration chamber responsible for validating government bills, whose real leader is none other than the President of the Republic. They are therefore perceived as elections with no real stakes.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, by provoking the constitution of a coalition of the left, baptized Nupes, wanted to raise a major issue, likely to shake up the usual functioning of the institutions. His disruptive slogan (“Elect me prime minister!”) is an injunction, addressed to abstainers in particular, to mobilize strongly in order to give him an absolute majority so that he can apply his program and prevent the elected president from apply his.

What is clearly targeted is cohabitation governance, which would give back to the parliamentary majority a pivotal role in the political life of the nation, in the spirit of a future Sixth Republic. Mélenchon therefore wants the same mode of appointment as his opponent elected president to rise to his level and to demonstrate that “another world is possible!” “. It is the whole problematic of the double, analyzed by Clément Rosset in Le réel et son double (1985, Gallimard) that is at play here; and if we follow the philosopher, this kind of aphorisms often turns out to be deceptive because they actually produce only an illusory duplication of this world.

The leader of Nupes did not win his bet, the left coalition not having obtained an absolute majority, or even a relative one. Abstention even increased by one point compared to the first round. Many reasons have been put forward to explain the extent of this electoral demobilization. But perhaps the underlying reason for such a situation should be sought in a major change in the role of politics in our late modernity.

A detour through the thought of Hartmut Rosa is necessary here. For the German sociologist, the essence of modernity can be captured in a single concept, that of acceleration, capable of systematically explaining a set of phenomena concerning all areas of social life. The German sociologist groups them into three analytically distinct categories. The first, and most obvious, is technical acceleration, which relates to the increasing pace of innovation in transportation, communication, and production.

The second form, namely the acceleration of social change, refers to the increase in the speed of changes in society itself, perceptible in the upheaval of its basic structures, notably work and family; these cardinal institutions find their stability increasingly threatened by the “compression of the present”. Finally, the acceleration of the rhythm of life refers to the existential experience of individuals of late modernity, prey to “time starvation” – they have the feeling that time is lacking or limited to them – insofar as they must “do more things in less time”.

This accelerating logic fundamentally changes our conceptions of the role, mission and possibilities offered to political action in democratic countries. This could, in classical modernity, when social dynamism was still far from the stage of excitement, assume a function of driving social evolution and building society; the idea of a social project was then a structuring and mobilizing idea.

But, in our late modernity (since the fall of the Berlin wall), politics, because of the chronophagy, in a democratic context, of the deliberative processes consubstantial with decision-making, sees itself pushed back far behind the accelerated changes of the economy, science and society. Its own temporality, requiring a certain durability and stability of social and cultural conditions, is no longer in line with the pace of social acceleration, which leads it to abandon this idea, which has become a zombie, of a social project. It is no longer in a position to claim anything, and is now condemned to react (to the pandemic, to the war in Ukraine for example) and no longer to act. Citizens perceive this, who often point to the vanity of political action.

We could therefore, and finally, give credit to the hypothesis of Hartmut Rosa, of a “deeper rationality of the voters who show, by their abstention, that politics counts less and less in the course of the story “. The growing volatility of the electorate would therefore be a phenomenon linked to social acceleration, which attenuates the scope of the idea of a decadence of civic duty.

Jean-Louis Robert, Sainte-Clotilde (Reunion)