She left the house not very enthusiastic. Even with a vague uneasiness. There is an atmosphere of sadness and abandonment here. The place has been empty for years. Despite the wide open windows, the smell of humidity does not dissipate. She finds the wallpaper hideous, the paint is peeling, the slats of the parquet floor uneven, damaged, creak at the slightest step. But she discovered the garden. A wasteland with box trees, rosebushes overgrown with brambles. The ivy attacks the trees. The paths disappear under the mosses. The orchard is a wild grass meadow. Yet the whole keeps the marks of a wise ordering, of a harmony of yesteryear. Finally, above all, at the time of turning back she saw the mock orange in the hedge. A big bouquet of white flowers whose perfume, for a moment, enveloped her. So, on her way back, she just said to her husband who was waiting for his decision, “Let’s take it.” »

A new life

Hélène Millerand’s new book tells a gently intimate story, a family story, that of her parents, a story of stuck moments, and also a story of passing time. The house is a large building planted in Sèvres, to the west of Paris, on the edge of the Saint-Cloud park. It’s suburban chic, but it’s suburban all the same. Jacques and Miquette go there a bit dragging their feet. They are in their early forties, he barely older, she barely less. We are at the end of May 1945. For them, the era of recklessness has long since ended. They led the way in the 1930s. Golden Youth. She is from the family of Lazard bankers, he is not really rich, but he can claim to be the son of a President of the Republic. Between Paul Deschanel and Gaston Doumergue (who remembers?), Alexandre Millerand indeed exercised the function from 1920 to 1924.

The war and the Occupation swept away everything. There is no more money. And mourning has hit them hard. Denis, their 2-year-old son, succumbed to leukemia in 1942. Christian, Miquette’s father, was arrested as a Jew and interned in Drancy before being deported to Auschwitz where he was gassed in July 1943. In April , Jacques’ father is also dead. They have three grown daughters. The fourth will be born in August. A new life awaits them in Sèvres.

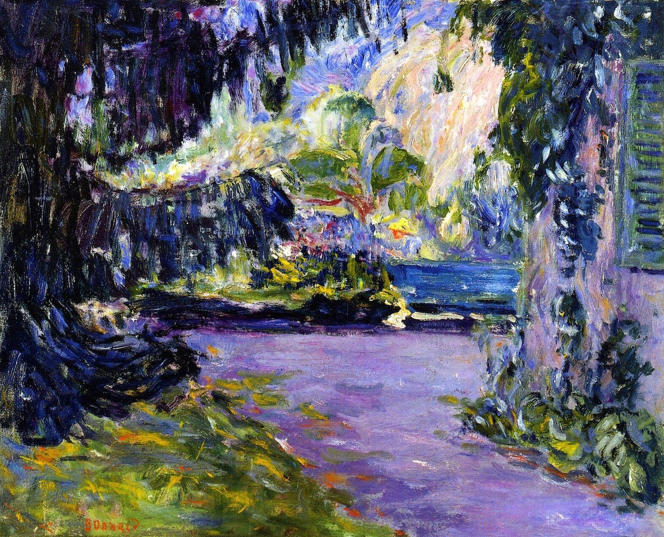

In two previous stories, Bistros et Gauchère (Arléa, 2016 and 2018), Hélène Millerand had already mentioned her parents and the house. From this house, she makes, with 27, rue des Fontenelles, a character in its own right. She draws an endearing portrait of it. For her, it all started there. In the crooked staircases, the many rooms and their nooks, in the escape of the vast garden. These are the places where she grew up. The cold building from the beginning has become a home. His book gives pride of place to those who have given a soul to these walls.

something broke

At the Paris courthouse, Jacques sits as a benevolent judge, he is considered “a light-handed magistrate”. When he is moved, his hands actually tremble, but never when he is playing billiards. He is asthmatic and a heavy smoker. He lives surrounded by books and considers Mérimée, whose Correspondence he reads and rereads, as his “best friend”. As a young girl, Miquette would have liked to be a painter. But at home, it was not done. Besides, she got married. Elegant, simply distinguished, she takes care of herself, for others and also, no doubt, for a certain idea she has of herself. She stands. But something has broken since his mourning. This father murdered by the Nazis made her intolerant of intolerant people. A trifle bristles her. She calms down with those she loves, she listens to the music of Mozart, Schubert. She sings. And then she gardens, almost every day.

27, rue des Fontenelles is written on the edge of memories, on the very edge of emotion. The text is a quiet thanksgiving. “They were my father and my mother from all eternity, and forever,” writes Marcel Pagnol at the beginning of My Father’s Glory (1957). Hélène Millerand accompanies her family to the end. She entrusts their memory to “the young guard”. The shutters of the Sevres house are closed now. Someone should take care of the garden today.

Extract

“They got used to going up and down the floors for a yes or a no, accustomed in the winter (…) to put three sweaters on top of each other, two pairs of stacked socks and neck warmers that one climbs on the nose to pass from one room to another, they have become accustomed, in the spring, to being awakened at 5 o’clock in the morning by the chirping of birds, accustomed to hearing the whistling in the middle of the night freight trains whizzing by who knows where, accustomed to hurrying to pick the cherries before the birds have swallowed them all, accustomed to eating apple and pear compotes from October to March until no more power (…). For the child who had just been born, the house was not the problem, the little girl first had to get used to living at all, which is another matter. » 27, rue des Fontenelles, pages 17-18