Among Tiffany’s vintage treasures

With their diamonds, the reflections of which make the eyes blink, their marble-sized stones and their precious settings, the houses of fine jewelry like nothing more than to amaze the spectator. Acquired by LVMH in 2020 for a staggering amount – 15.8 billion dollars, the record acquisition to date for the entire luxury industry – Tiffany

Kunz, his first gemologist

The New York house brushes and polishes its history for the occasion, shines its jewels and recalls its signatures. Its Setting solitaire, with a diamond perched on a six-claw setting, sits enthroned in the heart of a vast blue room – this famous Tiffany blue, registered with Pantone under the number 1837, the year the jeweler was founded. Or her Tiffany Diamond necklace, weighted with a 128-carat yellow diamond worthy of a ping-pong ball, worn by Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Diamonds on the sofa, 1961) and highlighted at the end of the exhibition . Blake Edwards’ film even has a dedicated room, with an annotated original script and a black Givenchy dress worn by the actress on screen.

But, beyond these highly Instagrammable masterpieces, the event above all allows you to discover pieces from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century that are rarely shown to the public. It highlights their creator, George Frederick Kunz, the jeweler’s very first gemologist, who also discovered kunzite in 1902, a rare pink gemstone to which he gave his name. “Kunz was truly a pioneer,” says Victoria Reynolds, the current chief gemologist. “With Mr. Tiffany, they wanted to establish themselves as American jewelers, using stones from the United States, an unusual approach at the time. »

Thus she points to a necklace made of oval, green, purple, orange, pink or yellow tourmalines, between which zigzag lines of gold: “These stones come from the State of Maine. Two steps away, she stops in front of a Japanese chrysanthemum brooch, a strong influence at Tiffany at that time. The leaves are gold paved with diamonds and the petals, “in elongated freshwater pearls, imperfect in their shape, called dog’s teeth, were probably unearthed in the Mississippi river”, continues the gemologist.

Brooch Orchids

In recent years, Tiffany has promoted the creations of Jean Schlumberger who, from 1956, represented flora and fauna under a whimsical spectrum, all birds with ruby eyes and strawberries with golden achenes. Early 20th century jewelry reveals a much more realistic approach.

Thus, on orchids designed for the Universal Exhibition of 1889, the pistil and stem are diamond-cut, but the petals, in extremely fine enamels, seek to capture the flower as close as possible to what it is. “At the time, this flower was reserved for the wealthy, for those who could bring it to them or for those who had a greenhouse,” recalls Victoria Reynolds. When Tiffany made about forty species of orchids in brooches, the clientele loved it and it happened for about ten years afterwards. »

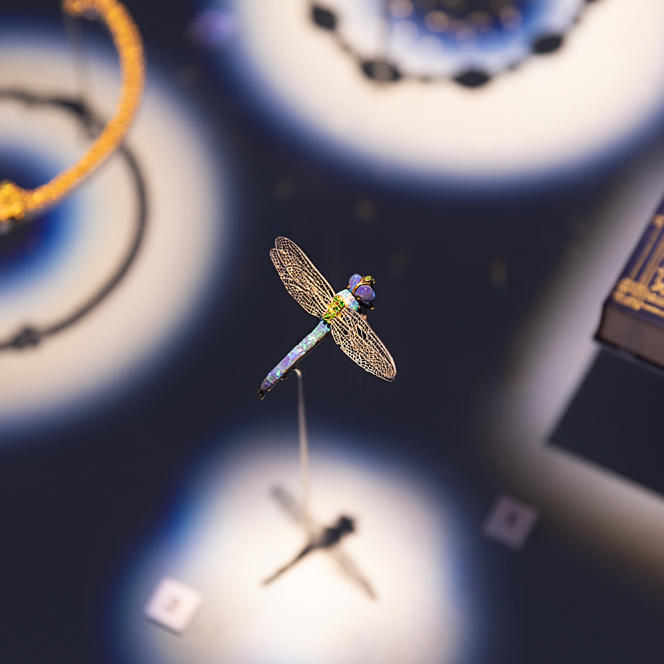

Similarly, a gold and platinum brooch dated 1904 and designed under the direction of Louis Comfort Tiffany, the founder’s son, depicts a dragonfly with no superfluous stylistic effect. Its translucent wings are translated by an extra-fine work of openwork gold; its body, with its iridescent reflections, by a string of rectangles of opal – “one of my favorite stones”, smiles Victoria Reynolds, pointing, in the same window, to a black opal which serves as a pendant for an adornment of Egyptian inspired.

What power do these archives, usually stored in vaults in New Jersey, have over the gemologist, who contributes to contemporary collections? “They oblige me. They push me not to let go in terms of stone quality, color, size, clarity,” replies the American, one of the few among the brand’s senior staff to have retained her position since the acquisition of LVMH. She has also worked for the studio and the commercial teams, and is celebrating her thirty-fifth year with Tiffany, which she joined when she left college. “And I’m far from knowing everything, it’s only just begun!” Kunz, his predecessor, had worked there for five decades.