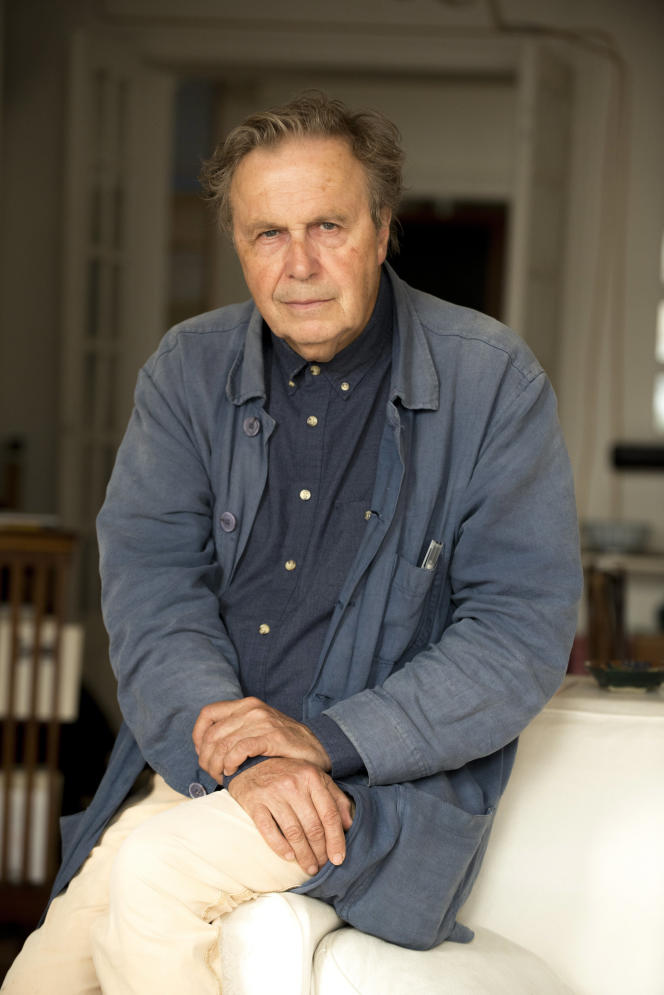

Jean-Christophe Bailly does not like to be considered a jack-of-all-trades. Writer who “does not write a novel” – he specifies at the outset at the “World of Books” in the Parisian café where we meet him -, poet, essayist, playwright, publisher, former professor of the National School superior nature and landscape of Blois… It is difficult to define what constitutes its territory. The real, no doubt, which is at the heart of his attention, the taste for wandering and the desire to “go beyond the particularities of this or that genre”, he explains.

In his abundant bibliography (born in 1949, he published his first book at the age of 18, in 1967), one can be struck, even confused, by the extreme diversity of the subjects of his books. We remember, for example, an essay published in 2007 on the animal cause (Le Versant animal, Bayard), where, in magnificent language, he describes “the quality of silence” of animals, the richness of their worlds and the sensitive and enigmatic link that connects us to them. “While writing this book, I had touched something of this world, moved to tears,” he says. In 2011, he published a very personal book on his experience of France (Le Dépaysement, Seuil), made up of stories of walks through France. A book that questions the notions of identity and memory inscribed in our spaces.

“Like a photographer in front of the world, you have to frame it”

When asked about his insatiable curiosity, the writer seems somewhat sorry. “I try to be interested in a lot of things. Then he pulls himself together. Corrects itself. “But, actually, no. I don’t try. I’m interested in it, actually. And I’m even often forced to limit myself. »

After a brief moment of silence at the end of which he seems to be suddenly seized by an idea or an image, he continues. “Take the line fishing. To tell you the truth, I never really cared about it. But it is absolutely thrilling. She questions the world of fresh water, that of fish and the origin of rivers. If you analyze the life cycle of wild salmon, it’s extraordinary. He leaves from above and returns to die where he was born. This kind of living phenomenon fascinates me. But, at any moment, one can panic at the extraordinary speed with which meaning continuously self-produces. So, like a photographer in front of the world, we have to frame it. »

The question of photography, as a medium and a model of writing, is at the center of his new book, Une Éclosion continue, which brings together numerous texts written over the past twenty years on the occasion of prefaces, conferences, interventions in schools. of art, etc. Bailly is accustomed to this kind of book whose structure is not only based on a compilation of writings, but on a “tile”. In each chapter, we find this fascination of the writer for photography, which can suspend time and show a silent fragment of reality. “Each of these cuts acts as a caesura and as an outbreak: through the choice of moment and setting, an eruption of meaning is delivered each time,” he writes. It is undoubtedly the writer who has the task of seizing these still images by bringing them into the great movement of language.

“What I saw I had to bear witness”

The origin of this passion, Bailly identifies with “early childhood”, when he collected images found in boxes of chocolates. Also, he says that his father, a tiling contractor, was close to the painter Jacques Monory (1924-2018), who introduced him to a new visual universe. “He was working at the time for the publisher Robert Delpire. At Christmas, he gave us books. That’s how I came to know the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who immediately fascinated me. But it was above all a family drama that had definitive consequences on his relationship to the world and to images. At the age of 12, his father suddenly lost his sight. “I suddenly started looking at the world a bit at her behest,” he says. “So, did you go there? And what did you see?” he asked me. My attention suddenly increased tenfold, with the idea that what I saw, I had to testify. »

In the formation of his gaze, before photography, there was first his deep affection for painting. Retrospectively, Bailly confides that he already looked, without knowing it, at the canvases like photos. It evokes Saint Jerome and the lion (1502-1507), a famous painting by Carpaccio in which we see the saint bringing a lion back to his monastery, to the horror of monks who are painted fleeing, as if in a freeze frame. “It’s quite amazing how the idea of the snapshot precedes its physical reality,” he says. This analysis of the nature of the still image is older, but from the moment I became more interested in photography, it is in this direction that I went. »

When Jean-Christophe Bailly speaks of images, they arise like ricochets. Each seems to surf on another, without his interlocutor finding himself drowned in these multiple references. Because the eye of the writer is obsessed with the tangible and the sharing of the sensitive. “Photography feeds my need to embrace reality, or to touch it. When I was younger, I was deeply marked by the poems of Cesare Pavese [1908-1950] and his “need for the concrete”, as he claimed. »

In front of a photograph, if what it gives to see is often lost sight of, Bailly once again becomes his extreme contemporary thanks to the dialogue he establishes with it. “The amount of time it catches is minute in terms of duration, but in terms of trace, it can be huge. It’s amazing what a photograph can catch! As in this snapshot taken by Charles Nègre in 1851, which shows three young chimney sweeps walking along a Parisian quay. “It’s an amazing photograph!” What it offers us is colossal, because there is Paris behind them, the Paris of Baudelaire. Besides, these three children are not dead, they are still living before our eyes! »

“The possibility of a permanent emergence of meaning”

Contrary to a rehashed idea that equates photography with a relic (Maurice Blanchot pointed to its “cadaverous resemblance”), Bailly considers it a living force whose destiny depends on our gaze. “The living that has been captured is not dead as it is, it itself becomes something latent; it itself becomes the eventuality of a permanent emergence of meaning. These are the signals that interest the writer and provoke his desire to write.

By dint of having rubbed shoulders with it so closely, has photography changed its relationship to language and its perception of the world? He smiles mischievously as he shows us a small black notebook: “I’m never walking around without this camera again.” Jumbled up, he jots down useful addresses, things taken from life, like snapshots, impressions of travels. Without any particular intention or hierarchy, he writes daily in this notebook, no doubt to fight against “the specter of mental decay”, he specifies. “In the humblest notation, as in a photograph, there is always something that carries incredible index power. Still, I’m envious of how easily the photographic catches the real, like a chameleon gobbles up an insect. On the lookout for these fragments taken from the rustle of the world, the distracted and concentrated gaze of Jean-Christophe Bailly seems to seek its own path to contemplation.

Journey

1949 Jean-Christophe Bailly is born in Paris.

1971 Beyond language. Essay on Benjamin Péret (Eric Losfeld).

1985 He founds the “Detroits” collection (with Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Michel Deutsch), published by Christian Bourgois.

1991 He signs, with Jean-Luc Nancy, La Appearance. Policy to come (Christian Bourgois).

2007The Animal Side (Bayard).

2008 The Moment and its shadow (Seuil).

2020 Imagery (Threshold).

Critique

Reserve of meaning

Jean-Christophe Bailly’s new book, Une éclosion continue, continues a reflection on photography begun in two previous works (L’Instant et son ombre and L’Imagement, Seuil, 2008 and 2020). It is a book on time, which is the main resource of the medium; this time that we do not really see pass, and whose photography, because it interrupts its movement, offers us a naked and abyssal image.

The writer’s idea, from which he builds chapter after chapter a thematic exploration of photography, is based on these questions: how can a still and silent image generate as many meditations as daydreams? Where does its store of meaning come from that a gaze can release by sheer force of attention? “What she captures is not just this or that moment (…) it is the way in which this moment – and everything that constitutes it – has been poured into time (…)”, writes Bailly.

This prodigious affair of time is embodied, for example, in the infinity of modes of the gaze (its “tempi”) that we experience every day, without realizing it, and that the work of photographers exemplifies. Precious pages are thus devoted to the works that the writer admires: those of Bernard Plossu, Denis Roche or Valérie Jouve. Despite their difference, these photographers practice an art without aesthetic excess, anchored in reality, in search of a stylistic intensity which is also that of Bailly in this very beautiful essay.

Extract

“Most of the time, the visible is not really seen, we just walk past it and realize that it is there, still there, still there. For example, it’s a recurring scene in noir novels: in an office, the hero, weary, pushes aside the slats of a Venetian blind and checks that, outside, the city still forms, with its streets and its lights, its heavy and perhaps blinding sky, the immovable decor, where, like everyone else, it is caught. Nothing is targeted or expected, it is a reflex gesture, a blank quote where the real appears only to disappear immediately, a bit like when from a commuter train you carelessly cast a glance at the familiar landscape. which scrolls. » An outbreak continues, page 17