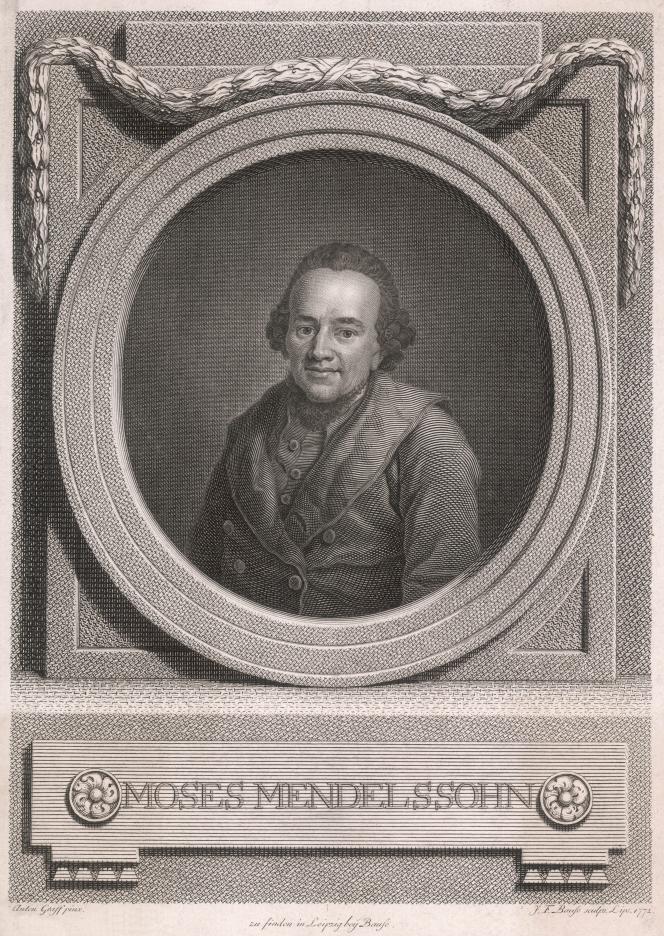

A solid contempt for the Enlightenment is now commonplace in many intellectual circles. It is enough that a thinker has displayed his confidence in reason, that he has worked for tolerance and believed in the existence of the universal to appear suspect. However little he hoped for equality and worked for emancipation, he will be willingly attributed a responsibility for all the evils of the earth. For this type of exercise, Moses Mendelssohn is an ideal target. Here indeed is an unparalleled historical figure: a Jew in the Prussia of the Aufklärung, he laid the foundations for a peaceful coexistence of cultures and religions. No doubt the history that followed took these horizons away from us. All the more reason to rediscover them.

The sum dedicated by Dominique Bourel to the life and work of this philosopher, to his time and to his various environments, is to be read to become aware of the lost continent where the love story of the Jews and of Germany. Mendelssohn was both initiator and actor of this extraordinary symbiosis. To become aware of this, you have to follow, with Dominique Bourel as an inexhaustible and unbeatable guide, the journey that made little Moses, son of Mendel, who was a scribe in Dessau, a great author whom his contemporaries nicknamed the “German Plato”, the “Socrates of Berlin”, the “Luther of the Jews”. Exceptional destiny of a modest man, who worked all his life in a silk factory, while being read by Frederick II and Kant with the greatest attention.

Self-taught genius

It was in 1743, at the age of 14, that he arrived in Berlin. Until then he had received a traditional Jewish education, learning to read Hebrew by deciphering the Scriptures. It is by his own means that he will gradually learn French, English, Latin, later Greek and a few other languages. To earn a living, the young man became a tutor, then an accountant in a silk factory, the management of which he would later be entrusted with, which he would then assume without interruption. “I’ve never been to college or heard a lecture in my life,” he said.

This did not prevent this self-taught genius from reading Spinoza and Leibniz, and Baumgarten, and Wolff and all that Germany of his time had in mind. “Breaker of ideas”, he first made a name for himself through his activity as a literary critic, which he began young, pushed by his friend Lessing, and which he continued almost until his death, becoming one of the most influential pens in Europe. In 1767, his Phädon, a dialogue on the immortality of the soul which updates that of Plato, was a rare success. It is translated into ten European languages. Many people think, as Kant himself writes in the Prolegomena, that “it is not given to everyone to write (…) with as much depth and at the same time as much elegance as Moses Mendelssohn”.

What binds him to Judaism? Why not convert to Christianity? These are the questions posed to him. A bad imbroglio, around Lavater, leads to a more brutal dilemma: whether he proves where Christians are wrong, or whether he submits. Mendelssohn’s response is beautiful and dignified: “I do not understand what could hold me back to a religion which looks so strict, and which is so despised by all, if I were not convinced in my heart of its truth. His position is both clear and unaggressive: he refuses to criticize Christianity, remains faithful to the religion of his fathers and nevertheless wishes that, without being confused, the two can agree: “In what blessed world would we live- us, if all men accepted and lived according to the holy truths which the best Jews share with the best Christians. »

This episode, which ended in 1770, marked a turning point in Mendelssohn’s life. He now devoted himself almost exclusively to Jewish studies, undertook a new translation of the Bible into German, different from that of Luther, and which earned him the hostility of some of the rabbis. He also works very actively for the political emancipation of the Jews of Europe, starting with those of Germany. There is no shortage of work: “In some dear cities of Germany, even today, he writes, no circumcised is left – even if it is declared – unattended during the day for fear that he cannot pursue Christian children or poison a fountain. »

At the death of the philosopher, the situation is very different. It will be even more so in the next generation: the dynasty he founded, where bankers, musicians and lawyers meet, embodies the brilliant Judeo-German culture that flourished in the 19th century. The one the Nazis will hate and murder. Dominique Bourel, who has read the smallest brochure and moves easily in a whirlwind of minute details, happily evokes this vanished world.