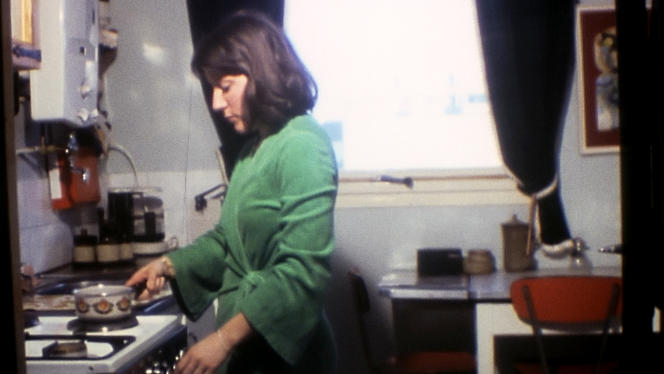

In faded images from a 1960 home movie, a young couple look radiant on their wedding day. They are the parents of Michèle Dominici, director of this documentary devoted to the rarely treated history of housewives. Based on intimate stories, amateur films, excerpts from television programs and commercials from the 1950s to 1970s, the final result is particularly moving.

“The idea for this film was born from a sentence uttered by my mother, says Michèle Dominici. She wrote her Memoirs but her story ended the year of her marriage. When I asked her why, she said, “Because after that it’s not interesting anymore.” A graduate of Sciences Po and a law degree, she stopped everything. »

Thanks to the Autobiography Association (APA), which collects accounts from anonymous people, the director found unexpectedly rich diaries in which women recount their daily lives. And documentalist Christine Loiseau has toured regional cinematheques, looking for unpublished family archives.

Throughout the documentary, excerpts from these writings illustrate the disappointments and hopes of these housewives. “How did I get here? To this fatigue, this boredom, always the same gestures. What happened to make my life so slip away from me? asks Anna. In post-war France, the place of most women was at home. “By nature, a woman is better suited to be at home,” ventured a man interviewed in a 1953 radio program. The entirety of the housewife’s days belong to others: husband and children.

“When I see the ads, I get angry. I do not find myself in this ideal of a happy and fulfilling wife at home,” wrote Francine in her diary in the late 1950s. It was not until 1965 that the French woman finally had the right to own her own checkbook and to open a bank account in his name. “When I talk to my husband about freedom, he asks me why I’m complaining! writes Ruby.

consumerist propaganda

The 1960s were also those of consumerist propaganda. Technological advances make it possible to replace old household chores, and the housewife, through advertising, must become the chief consumer. An illusion that doesn’t fix anything: “I feel like I’m dissolving. I no longer have an intellectual life, everything that interested me as a student, history, politics, philosophy, seems so far away,” says Anna.

At the end of the 1960s, new images of women emerged: active, independent, ambitious. And this societal earthquake upsets the fragile balance of homes. “I sometimes feel like my husband doesn’t see the world changing. It’s like all fun outside of him and the kids is off limits to me,” Ruby says.

A television show from the early 1970s shows a stay-at-home mom chatting with her two daughters, who have no intention of living like her. “We thrive more in a job than at home,” says one in front of her mother, doubtful.

The end of the “glorious thirties” also marks the end of the dominant societal model of the housewife. Too late ? “I really liked what Simone de Beauvoir said about old age: a woman can use her age as a pretext to avoid the chores that weigh on her. She knows her husband too well to be intimidated by him anymore,” Ruby concludes.