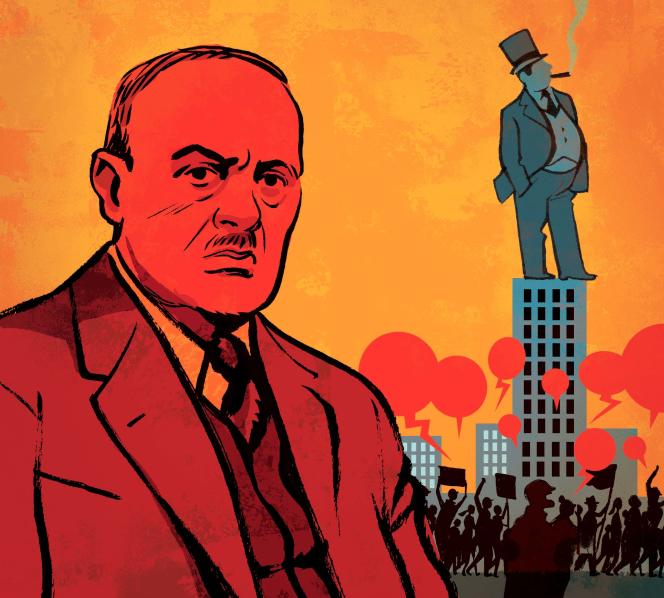

When “angry citizens” roam the streets of Western democracies, isn’t it urgent to think deeply about the notion of resentment? Because it cannot be reduced to an affect or temporary outbursts. Perhaps this revenge long delayed by powerlessness expresses a structural springboard of our time that confronts us with a very bitter truth: more than progress, decline, weakening, diminishing of our capacity to to act and to feel, or even the sadness of metropolises, however more and more profuse in offerings of culture and pleasure, characterize our modernity. This is the early assessment of L’Homme du resentment, by the German philosopher Max Scheler (1874-1928), now republished in a revised translation.

It is true that the first version of the text dates from 1912 and that one feels the atmosphere of intellectual mobilization in view of the clashes to come. The rolling fire attacks on the egalitarianism inherited from the French Revolution (“the greatest discharge of resentment in modern times”), the outbursts against universalism, utilitarianism and modern humanitarianism – criticisms of which the thinker – even will regret the excesses retrospectively – can only disturb the certainties of a 21st century reader. But the cruel portrayal of bourgeois society, capitalism, and “modern morality” often hits the mark. For example, when Max Scheler is already lamenting “the tendency of industrialism to make the world a desert”.

Style both fiery and rigorous

There is no doubt that Max Scheler also draws his skepticism from his Catholic faith, which he adopted in 1899, but with which he broke at the end of his life. In The Man of Resentment, the philosopher puts his fiery and rigorous style at the service of a Christian morality which he intends to cleanse from the sentimentality of “social Christianity” and the positivist beliefs typical of the “stupid 19th century”, so that it rediscovers the energy of ancient Christianity. Some of his vituperations recall the harsh writing of Christian antimodernists in France, such as Léon Bloy or Georges Bernanos. In any case, it seduced a good number of French people from all walks of life, including Sartre, Merleau-Ponty or Paul Ricœur. From the 1920s, some of his writings were available in French. Thus, The Man of Resentment was published by Gallimard in 1933. The author of the translation remained anonymous, but we know that it is the work of the Dominican and orientalist Jean de Menasce (1902-1973) .

Since then, the star of Max Scheler, founder of an important current of German thought in the 20th century, philosophical anthropology, today in full rediscovery in France, has faded, all the more so as its theoretical, political reversals and religious make it difficult to situate. Initially neo-Kantian, Scheler approaches Edmund Husserl and his phenomenology. Then, under the influence of the philosophies of life, Bergson in particular, he will put at the center of his thought the situation of man within the living, as well as action and no longer the theory of knowledge. If he writes sophisticated essays, but intended for a wider audience, like The Man of Resentment, it is due to the vagaries of a turbulent private life which, for a time, push this academic to produce intervention writings. Scheler, admired by the young Heidegger, indeed lost his venia legendi (“permit to teach”) in 1910, after being caught in a hotel with a married woman.

The collective ferment of decadence

Following Nietzsche and the economist Werner Sombart (1863-1941), Max Scheler sees in resentment the collective ferment of a decadence which began, according to him, as early as the 13th century, with the advent of a class defined by its resentment against the nobles and competition: the commercial and calculating bourgeoisie. But if he considers himself close to the Nietzsche of The Genealogy of Morality, Scheler believes that the philosopher is mistaken in targeting Christianity. The love advocated by the Christian, far from being a “slave morality” concealing under an alleged love the hatred of the weak for the strong, constitutes indeed a positive amplification of the person, who surpasses himself in the encounter with his God and not “this colorless love of anything, which Nietzsche was right to jeer and fight”.

To lament that our present is reduced to “a society of logicians parked in a machine room” must it be done at the cost of the exaltation of castes, of chivalry, of warrior heroism, with devastating consequences, or of the idea that living nature obeys an “aristocratic principle”? Probably not. But, by exhibiting its flaws, The Man of Resentment, this classic of philosophy, also lends us the strength of its diagnosis.