Before being the victim himself one morning in January 2015, Cabu drew barbarism. It was in 1967: aged 29, the cartoonist had accepted an order from the weekly Le Nouveau Candide to illustrate the good sheets of La Grande Rafle du Vel d’Hiv (Robert Laffont), a revelation book by Claude Lévy and Paul Tillard.

These two former communist resistance fighters – a medical biologist for the first, a journalist and writer who experienced deportation for the second – had investigated at length the operation of the French police which led to the arrest of nearly 13,000 Jews on July 16 and 17. 1942, lifting a veil over one of the darkest episodes in the history of France. Tormented by “this terrible book which will give [him] nightmares”, Cabu will produce sixteen drawings, which an exhibition at the Shoah Memorial allows you to (re)discover today, on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the tragedy.

It is not forbidden to wonder what the creator of the Grand Duduche, then star cartoonist of the newspaper Pilote, was doing in the pages of Nouveau Candide, a highly-rated magazine with Gaullist sympathies. “He had a family, the pot had to be boiled,” says his second wife, Véronique Cabut. Stakhanovist of the line, Cabu also collaborated, at the same time, for the Figaro, which had asked him to follow the trial of Ben Barka, the previous year. A tabloid before its time, Le Nouveau Candide was also distinguished by its sensationalist subjects, among which the Jewish theme served as a business. “Eight days of hell for the Jews of Paris”, “The Jews of Paris in the trap”, “The drama of the Jewish children”, he thus headlined on his front page, in April and May 1967, for accompany the publication of extracts from the book by Lévy and Tillard.

« Illustrations » grands formats

This “noisy editorial commission”, Cabu will “sublimate it (…) by his precise line, the finesse of his gaze and his sensitivity”, writes the historian and director of research at the CNRS, Laurent Joly, in the book-catalog of the exhibition (Tallandier, 56 pages, 18 euros) of which he is the scientific curator. As he did for the Ben Barka trial, and as he will soon do in Charlie Hebdo through his comic book reports, Cabu has abandoned pure caricature for a realistic style, sometimes close to photography or Italian neorealist cinema.

There is obviously no question here, for him, of making people laugh, or even be indignant, the BA-BA of any press cartoonist. Multiplying the techniques (pen, isograph pen, wash, charcoal, white gouache, glued paper), his large formats are indeed “illustrations” and not topical crobards. The absence of text, however, does not exempt his work from an artistic intention: to isolate the victims and the executioners in the same space of paper.

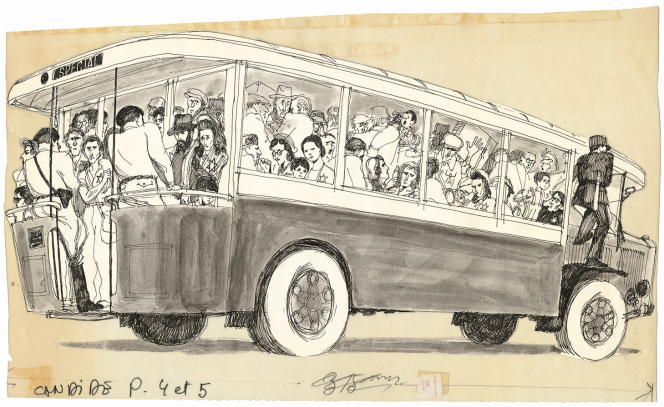

For this, Cabu takes care to avoid representing the slightest witness in the scenes he sketches: the arrests, the assembly centers, the transfers by bus, the internment in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, the train Austerlitz heading towards the Loiret camps… Only Jewish families of foreign origin appear in his drawings – men, women, children – and French executioners, mostly policemen, acting on orders from the occupier and Vichy. No outside observer is there to take offense or lend a hand, except for a totally apathetic Skytrain traveler. The process aims to send future deportees back to their solitude, but also to highlight the collective amnesia that has descended on this state crime.

The talent of the “Daumier of the 20th century”, as he would later be nicknamed, did the rest. Cabu knows the importance of looks in this type of exercise. A few strokes of the pen are enough to set up a color chart of expressions, ranging from worry to fear, from resignation to despair, without any tragic complacency polluting his line with absolute relaxation. A few collective scenes, in particular inside the Vél’ d’Hiv, where hundreds of characters swarm, are reminiscent of the touch of its master, Albert Dubout. A sequence of flight, in chiaroscuro, evokes Rembrandt.

personal memory

Obviously, Cabu did some documentary research before giving his first pencil strokes. Witness the wall advertisements of the former temple of boxing and cycling (demolished in 1959) which he faithfully reproduced. To think that the disastrous journey to Auschwitz began, for some, under signs touting Pernod anisette or articles from La Samaritaine amplifies the nausea.

But Cabu also used his personal memory, deemed infallible. He remembered the huge glass roof in the 15th arrondissement, visited at the age of 14 as the winner of a drawing competition organized by Cœurs vaillants, a Catholic weekly in which he read the adventures of Tintin. Coming from Châlons-sur-Marne (today Châlons-en-Champagne, in the Marne), the child was given a bicycle that day by the Archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Maurice Feltin, former support of Marshal Pétain during the Second World War. The young Jean Cabut will be invited to take a lap on a bicycle but will almost fall due to the banked turns. A few years later, studying at the Estienne school, the jazz lover would return to the Vél’ d’Hiv to hear Cab Calloway and his orchestra during the intermission of a Harlem Globe Trotters game.

Naturally, Cabu made some errors in his graphic treatment – errors due to the state of knowledge at the time when he drew. Collaborative militants of the French People’s Party thus make up the ranks of the arrest teams, victims attempt to commit suicide inside the velodrome itself: nothing confirms the veracity of these facts drawn from the testimonies reported by Lévy and Tillard .

The designer will also be inspired by the photo reproduced on the cover of the book, where supposed “snatched up” are seated on the track of the velodrome and not in the stands. Used incorrectly, the photo actually represented suspects of collaboration interned at the Vél’ d’Hiv at the end of the summer of 1944, as Serge Klarsfeld demonstrated in 1983. To date, there is only one proven photo of the 1942 roundup. Taken overhanging a row of buses, rue Nélaton, it was only discovered – by Serge Klarsfeld, too – in 1990, well after Cabu’s compositions.

The latter had applauded, in private, the speech delivered by Jacques Chirac in 1995 in front of the monument commemorating the roundup. A President of the Republic recognized, for the first time, the responsibility of France in the deportation to Germany of the Jews of France. Pillar of the Chained Duck, Cabu had drawn no drawing from this speech. Probably because it was tricky to flatter one of his favorite Turk’s heads. Perhaps also because the Vél’ d’Hiv roundup continued to haunt him, and it is sometimes difficult to laugh at everything.